Special thanks to Mosi for collaborating with me on this absolutely massive report; 0xPerp for all of the advice and feedback; Michael Rinko for actually reading this and giving feedback freakishly fast; Benjamin Sturisky for all of the reminders on topics I forgot to include and saving me; Velvet Milkman for making my writing sound less robotic in parts; Sanat for providing some necessary counterpoints to my arguments, and everyone else I talked with in the process of writing this.

What prediction markets are and aren’t

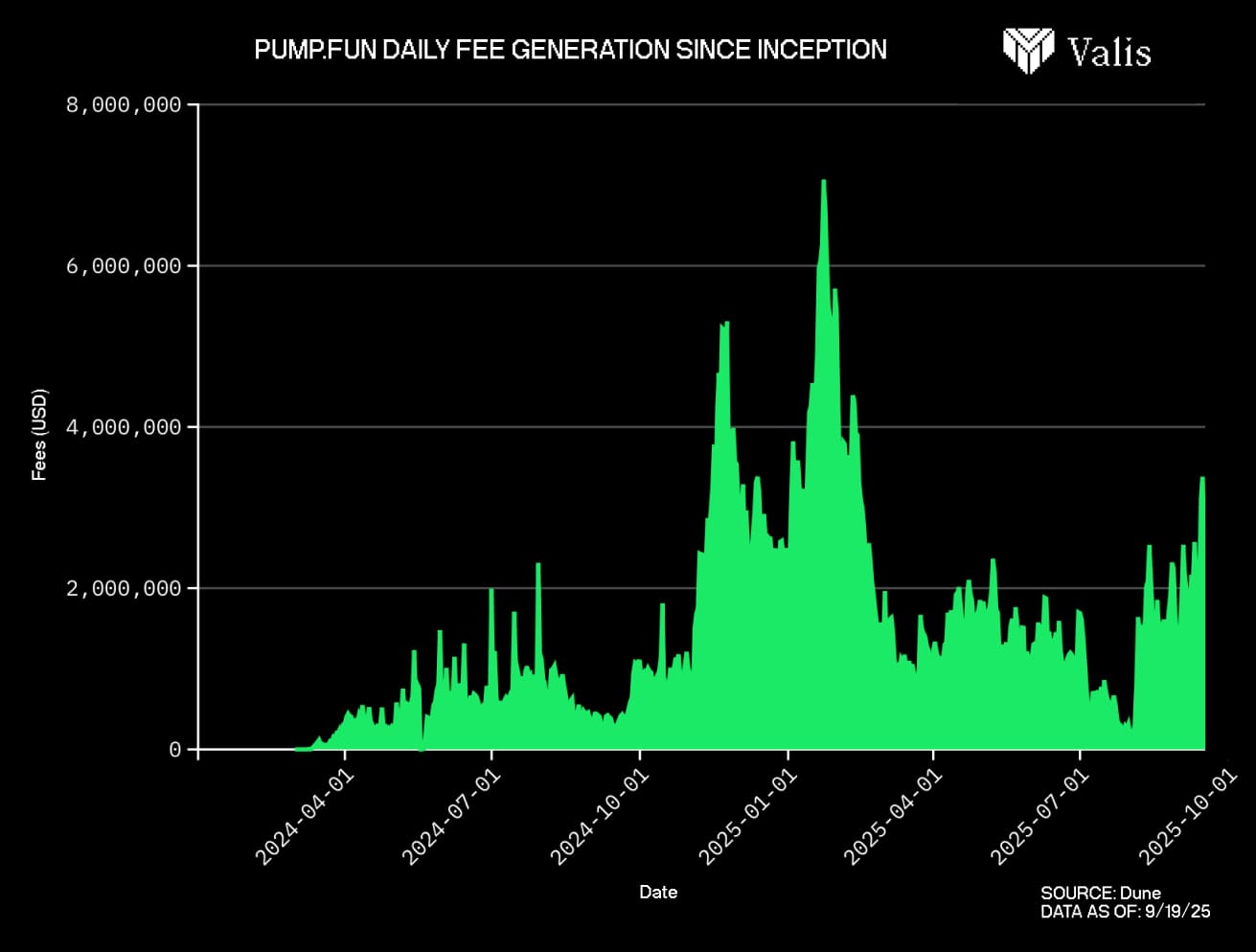

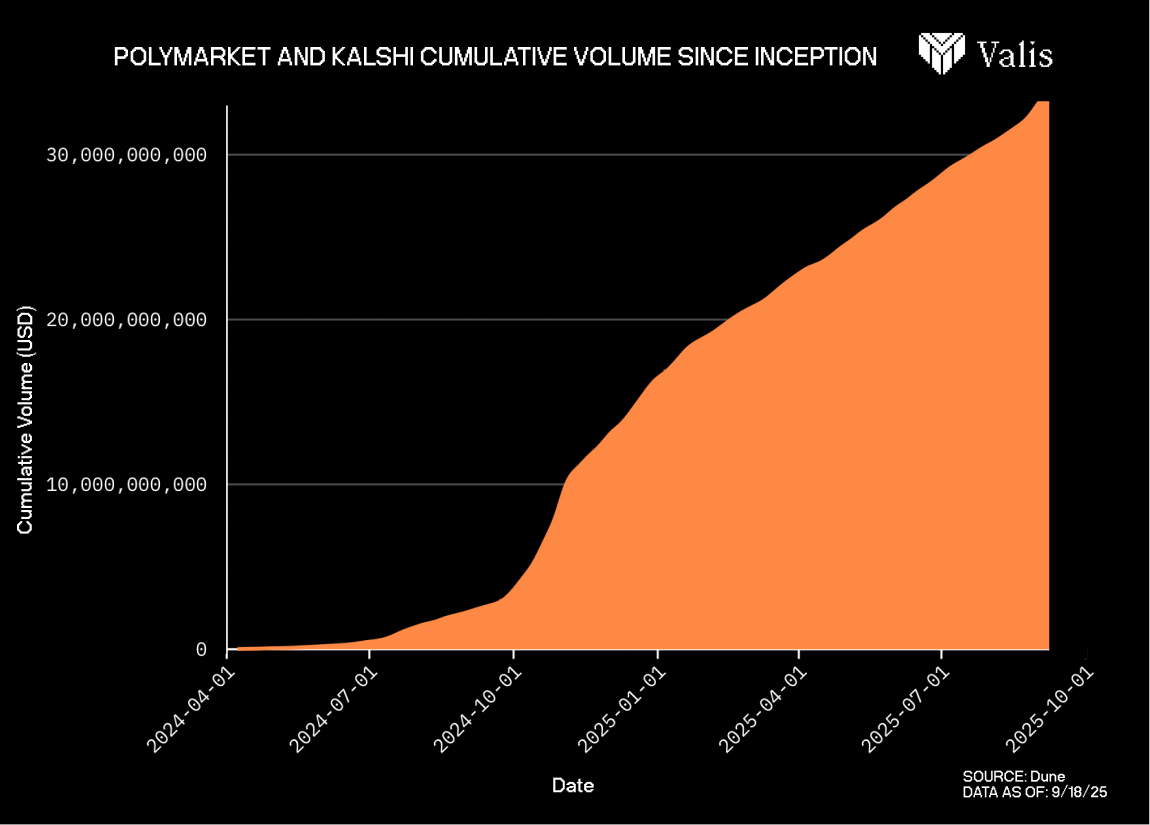

Prediction markets are everywhere. After the conclusion of the 2024 US Presidential Election, it was expected that Polymarket and Kalshi’s respective volumes would fall off a cliff as they’d done in years past. But that hasn’t happened, and our goal for today is unpacking why they’ve remained relevant and what can be expected if these volumes continue inching higher over the next 2-3 years.

For reference, Kalshi and Polymarket have processed over $35 billion of volume according to @dunedata since inception, and a combined $17.5 billion of volume in 2025 so far.

This warrants a deeper analysis, considering this is no longer a niche form of speculation for hobbyists or data nerds, but a readily available option for anyone with an internet connection. But even this already measurable success is just the beginning, and depending on who you ask, a drop in the bucket when considering what’s to come.

To quote @semajieth:

"Prediction markets have variously and recently been described as: the wisdom of the crowds in financial form, the most democratic financial market made yet, and simply the future of speculation."

There’s been an endless stream of surface level content flooding X every day for the past month, giving you lengthy analysis on anything you’d ever want to know about prediction markets and explaining how anyone can make money trading event outcomes with ease.

Rather than feeding you trade ideas or filling your brain with wishful thinking, we’ll give you a complete overview of the top prediction market platforms and how they’ve managed to get to where they are today, analyzing more niche areas of interest like market maker dynamics, distribution of volume and open interest across markets, historical accuracy across multiple venues, and many other foundational topics that will contribute to your better understanding.

At its most basic, a prediction market is a type of financial instrument that allows people to trade contracts tied to the outcomes of real world events, letting traders win if they’re right, or lose if incorrect.

That’s a very surface level explanation, and maybe you’re asking why this is any different from other types of investments, or what the innovation really is here.

People enjoy trading prediction market contracts not solely because of the payouts, but because of what they let you trade. Prior to the introduction of consumer-friendly prediction market interfaces, if you wanted to put your money on an event, an opaque OTC desk or random internet counterparty was the only avenue for placing this bet. Today, it’s easier than ever to read a headline, scoff at the journalist’s opinions, and throw $100 on the exact opposite outcome of whatever you just read.

In Camilo’s words,“they distill the complexities of investing into a single equation of risk, return, and probability” which is a great way of saying that prediction markets make it so previously difficult-to-execute trades (that require complex financial instruments) are almost immediately accessible to the average user.

Robin Hanson is considered by many to be the father of prediction markets, largely due to his robust body of work covering futarchy, idea futures, decision markets, and other related topics. Much of his work can be found here. Despite these illuminating pieces of writing existing, many of which date back to the early 1990s, prediction markets were confined to a small corner of academics and nerds, existing as more of a pipe dream than a feasible financial instrument.

It took years but some unlikely names laid the groundwork for Polymarket, Kalshi, and every other company alive today. To name a few notable experiments courtesy of Adjacent Research:

-

Terrorism Futures were created by the Pentagon back in 2005

-

Google ran their own internal prediction markets

-

The CIA published a report analyzing prediction markets’ ability to enhance US intelligence PDF

It’s 2025, and prediction markets are a runaway success not because of what they are, but what they’ve been able to enable, and of course what could mean for global market structure.

What you can learn

Most of what you’ve heard about prediction markets is true, but there hasn’t been an honest attempt at mapping out the most important functions crucial to the continued success of these platforms. This report will answer the following and more:

-

How do market makers and liquidity providers operate across Polymarket and Kalshi?

-

What are these exchanges’ reward/incentive structures like?

-

How much of a concern is market manipulation and what’s being done to mitigate this risk?

-

Which markets are more likely to receive a higher distribution of incentives?

-

Why haven’t parlays or leverage seen more traction?

-

Can prediction markets predict the future more accurately than the best experts?

-

What aspects of dispute resolution need to be fixed?

-

How important is the CFTC and is a regulatory-first approach the path to mass adoption?

-

Is it feasible to compete directly with sportsbooks on sports-related event markets?

-

Why have dozens of crypto-native prediction market startups spawned, seemingly out of nowhere?

We’re taking a data-driven approach and pulling together dozens of hours of research to bring you the most comprehensive report on prediction markets to-date.

Before going any further, we must clarify some things.

This report primarily looks at usage across Polymarket and Kalshi as they are the most widely used venues. This is not to say that incumbents can’t be overtaken in the future, but rather their combined usage sums up the vast majority of prediction market activity >99% of notional volume & open interest, and analyzing their differences will shine the most light on the future of the space.

We aren’t here to tell you that prediction markets are or aren’t the next big thing. We’ll make use of dozens of sources across numerous independent publications and reports, use quotes liberally, and present the information to you while refusing to take a side.

It’s important for research to be unbiased and walk a tightrope between obvious favoritism and the objective truth. The truth?All of the above questions are a lot harder to answer and can’t be found just by looking at the data.

-

Are prediction markets the next frontier for finance?

-

Are prediction markets just a more obfuscated form of gambling?

-

Are prediction markets only a side effect of humanity’s growing desire to speculate in new ways?

To quote Aashish Reddy:

“Prediction markets give us a way to harness the wisdom of crowds, and turn it into useful forecasts for decision-making. But I know from past conversations that you’re probably not convinced by this; indeed, you probably shouldn’t be, just yet.”

How prediction markets fit into a culture of speculation

Everyone likes to gamble. Whether it’s sports, scratch-off tickets, or slot machines, the global gambling market is massive and has continued to grow despite the reality that the house always wins. Since the legalization of sports betting in the United States in 2018, over $500 billion of volume has been done according to Legal Sports Report , generating tens of billions of dollars in revenue for states in the process.

You can’t watch a professional sports game without being shown moneylines, player prop bets, or betting-related predictions from TV analysts. Commercials frequently bombard you with propaganda distributed by these sportsbooks (namely FanDuel and DraftKings) directly, masking the toxic reality of gambling with endorsements from household names like LeBron James.

New York and New Jersey alone have made over $11 billion in tax revenue and the annual sum has grown exponentially in just seven short years. It’s unlikely sports betting is criminalized again given how lucrative it is to these states that allow it, though the negative externalities of widespread betting have not been considered.

We can make an assumption that gambling has more or less become an everyday occurrence for tens of millions of Americans over 30 million in 2023, presenting us with a world where gambling isn’t just allowed, but normalized.

Sports betting is the best comparison we have for prediction markets, and while it isn’t perfect, it will be used to present how and why prediction markets have become more popular. While prediction markets are structured with payouts resembling binary options, and sports betting is odds-based, the venn diagram of users converges and the thought process behind taking either of these bets can be viewed quite similarly.

People don’t want to learn how to make money, they just want to make money.

If a devout Republican had read a headline in October 2020 that Donald Trump’s probability of winning the election sat at 40%, they may have previously scoffed and complained that mainstream media is out of touch with their personal worldview.

At this time - just five years ago - the aforementioned individual was more than likely unaware of prediction markets and wouldn’t have known they could stake their money on something as important as the US Presidential Election, but we live in a different world today.

In late 2024, this same individual could have placed $100 on Donald Trump shares at $0.40 and hoped to return 2.5x their money assuming a successful win in the election, or watched their money evaporate as Kamala Harris shares settled to $1.00, but the outcome isn’t the point.

The core innovation of prediction markets is their ability to turn human beliefs into bets, letting anyone put real dollars on an opinion they believe is correct. This is human nature and it’s one of the reasons sports betting has risen to notoriety so quickly. Sports is a major part of many Americans’ lives, especially young men, which by and large are making up a larger share of sports betting volumes every year .

Quick aside, I can name dozens of friends and fraternity brothers from college that discuss sports betting constantly and place bets every day of the week that doesn’t end in a Y. This doesn’t come as a means of shaming anyone, but an observation from a 23 year old noticing a trend amongst peers.

Young men live and breathe sports, and it isn’t a stretch to say professional sports is quite high up on these individuals’ lists of hobbies or pastimes. If you spend countless hours outside of work tracking pro sports developments, watching games, and arguing with friends over the outcomes, it’s just as likely for you to then feel the need to make money off of this.

This same individual that feels strongly about the Philadelphia Eagles might feel equally as strong on whether Jerome Powell will cut rates, but lack the knowledge or a simple outlet to precisely bet on this via other financial instruments. The average dude would never message a sports group chat asking what everyone thought about the jobs report, but this same guy might actively chat it up on Polymarket’s in-market chat rooms.

The logic of making money from something you feel you have an edge in can be extended from sports to prediction markets, except for one small detail: the TAM is nearly infinite.

Whether it’s politics, global events, or pop culture, there is a market for something on Polymarket, and there’s a market for every type of person.

Leading avenues for speculation

Crypto hasn’t been discussed yet, so let’s get into that, as it’s a pretty popular technology and quite notorious in discussions related to speculation.

Buying crypto is easier now than it’s ever been. For years you could have purchased Bitcoin (and other major assets) directly from Venmo, Robinhood, or even in the form of an ETF through your brokerage account, and while getting crypto on-chain is still a bit messy, it’s within reach in probably under ten clicks for someone that knows what they’re doing. This has led to significant growth of digital assets trading, proliferation of stablecoins, and the obvious eye-watering performance of assets like BTC and ETH over the last decade.

Across crypto’s largest exchanges, trillions of dollars of volume is done each month across a number of centralized and decentralized venues. The market for digital assets continues to resemble more sophisticated markets like equities or commodities, while the pool of traders and blockchain users only grows. We can make an argument that buying crypto, investing in crypto, or trading crypto on a shorter time frame is relatively easy and within reach for anyone with an internet connection, and that despite the utility accompanying many crypto assets, this is still an outlet for/form of speculation.

Going back to the point that prediction markets will become the next major avenue of speculation - similar to sportsbetting, 0DTE options, or memecoins - it’s easiest to compare the numerous frictions of retail user participation.

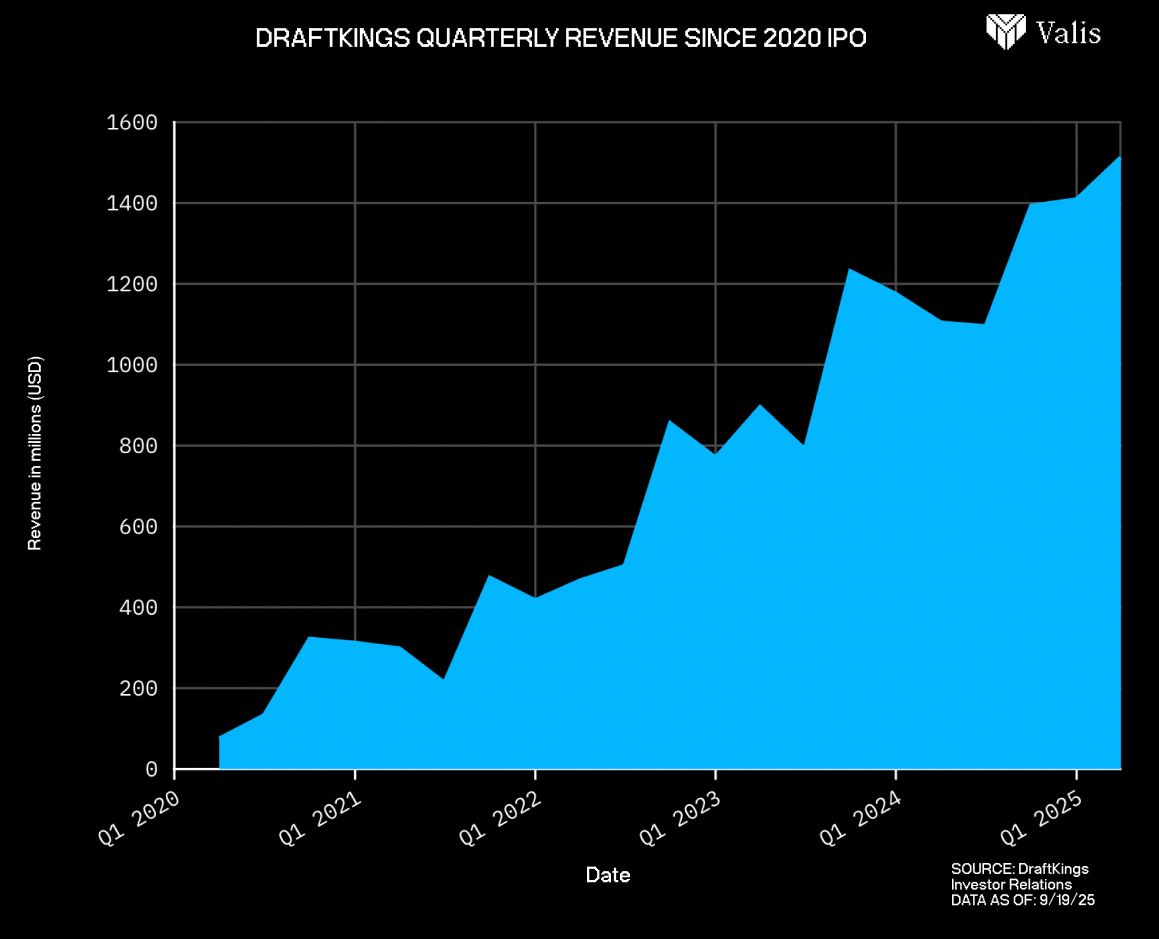

Signing up for a DraftKings or FanDuel account is quite easy and deposits can even be made directly through money transfer apps like Venmo or Cash App, making the temptation to just “place a small bet” all the more easy for tens of millions of Americans. We’ll discuss actual usage of these services quite soon, but DraftKings specifically has grown its annual revenue at a rate of 67% per year since 2020, with recent Q2 seeing over $1.5 billion in revenue. This growth also comes on the back of societal shifts, most notably the recent outflows of Las Vegas’ residents, businesses, and most importantly, its gamblers.

Robinhood has democratized access to stocks, crypto, and most importantly, options. You’ve probably heard of /r/wallstreetbets their absurd userbase, and the ridiculous amounts of money spent by retail traders on options contracts, specifically 0DTEs usually tied to memestocks.

But were you aware the actual volumes generated by retail option traders were quite high, with retail’s share of option trading peaking at roughly 48% via NYSE in 2023? That’s a ridiculous number, especially considering how complex the underlying mechanisms of a standard option contract can be, it’s a miracle so many willingly trade these.

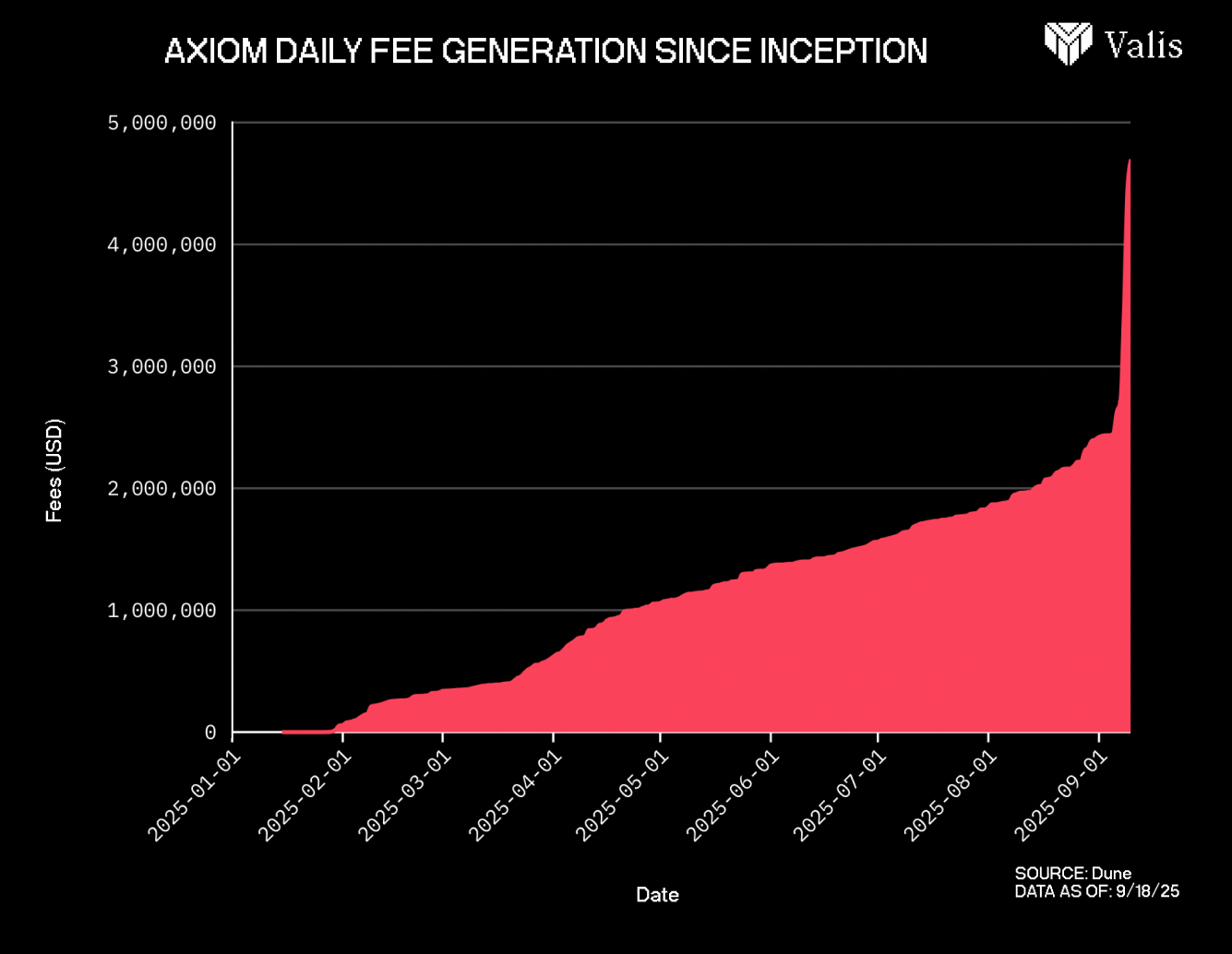

Memecoin trading on Solana is still hot and, at one point, was one of the most lucrative ways to hit a 100-250x for relatively little effort (assuming you managed to hit one at all). Venues like Axiom and pump.fun still bring in millions of revenue each month, though participation has tapered off a bit since their peak.

Despite the drop-off, it’s undeniable that memecoins represent a more hands-off approach to financial freedom for those with high risk tolerance and a desire to make it as fast as possible. More than anything, memecoins were the first example of retail traders getting heavily involved on-chain, with social media platforms like TikTok showcasing the hundreds of thousands of newfound traders willing to burn money in search of a gem.

What do these three sources of speculation all have in common? The venues used to enable speculation allowed for almost anyone to access a new form of trading or gambling without needing to spend hours learning how it's done.

Negative externalities of prediction markets

PMs are not perfect, in fact they already have negative externalities. Similar to traditional gambling, there’s a certain ‘hook’ on prediction markets. And even more so than trad casinos because now PM users might feel like they have an ‘edge’ over some markets. Furthermore, participants are also able to directly influence some markets, opens an interesting pandora box on influencing these markets. On the softer side we have people throwing dildos at WNBA games and the guy who famously stroke the superbowl, got fined but made around ~374k on his 50k bet.

On the more obscure side of this Pandora box, every market involving actions of a certain person are de-facto assasination markets. Take this Charlie Kirk case as a good example. The assassin could theoretically bet on this market, and then go on and kill Charlie Kirk to collect a payout. This is why ‘permissionless’ prediction markets are so hard, they essentially enable an economy in which anyone can permissionlessly hire a hitman without very little repercussions.

The psychology of prediction markets

Prediction markets are still in their infancy, and more work is needed before everyone can be onboarded, but their biggest underlying strength is the lack of prior knowledge or education needed by their user base to immediately participate. This could be attributable to the broad subject matter available to trade, the ease of selling a position prior to resolution, or even the more streamlined probabilities distinct from clunky sports betting odds - but the reality is it’s not that difficult to understand this financial instrument.

Human nature is wanting to be right and proving that someone else is wrong in the process. Whether it’s arguing with a friend or coworker over something trivial, like debating the winner of the Monday Night Football game or as crucial as fighting for your client’s innocence in a court of law, many important human interactions take the form of a binary option.

I’m right, you’re wrong. You win, I lose. Double or nothing.

Part of what’s propelled prediction markets into the public zeitgeist is this idea that everyone likes being right, and everyone likes making money - a prediction market venue like Polymarket or Kalshi is able to satiate this innate human desire to be right and provide the tooling to enable mass speculation on previously un-investable ideas, beliefs, or even strategies. Maybe part of what makes prediction markets so appealing is the simplicity of it, or how it connects with your brain more than stock prices or Option Greeks do. Being able to launch Polymarket and bet whether earnings miss by 5% or 10% is not only simpler, it’s more intuitive.

And that’s where we are today. Prediction market odds have been displayed on national television programs like CNBC and CNN, sports betting is commonplace, and prediction market growth has continued even after the 2024 US Presidential Election, atypical of the volume drop seen in years prior.

It’s table stakes for an analyst to argue for continued growth in volume or DAUs but how do you underwrite mass speculation occurring at an unprecedented scale, the birth of everything markets, and the potential formation of the 21st century’s newest financial behemoths?

Let’s temper expectations with some much-needed criticism.

Reducible Errors has an excellent post full of necessary rebuttals, quantifying what it means for a market to be good and the set of characteristics a market must possess to attain this title, these being standardized products, heterogenous participants, low transaction costs, and many participants.

RE does a great job highlighting many of the most glaring issues surrounding prediction markets and explaining why these products won’t see institutional adoption anytime soon, but the post fails to recognize many of the more qualitative benefits.

This idea that prediction markets and their binary nature make for a poor hedging instrument is definitely true, though only if we’re assuming a user base consisting entirely of financial professionals and elite market makers.

Prediction markets exist in some type of superposition.

On one side you have a ravenous horde on X calling prediction markets the natural next step for all financial markets, while the other side - composed of professional sports sharps - remains convinced it’s just another form of gambling, albeit a more sophisticated version.

“ES trades so much because people use it to hedge. They're transferring risk they don't want, and they're perfectly willing to pay a (small) price for the service the market provides. It's this activity that gives rise to all the trading we see in financial markets.”

It’s true that a financial institution would much rather hedge with S&P 500 futures than some prediction market with less than $5 million in volume, the same can’t be said for a pair of college roommates living in a dorm trading their $50,000 portfolio of crypto and meme stocks.

Of course these two college roommates might know futures very well, and understand how opening and managing a position works, but it’s a lot easier to deposit $5,000 onto Polymarket and open a hedge without the hassle, especially considering how much simpler a prediction markets platform is compared to the average experience that comes with trading futures.

Saying that prediction markets in their current state are unfit for institutions is obvious, but suggesting a list of things that need fixing to accommodate for this is non-obvious, explaining why you’re much more likely to read a glowing or scathing review of prediction markets.

Aashish Reddy wrote that even if prediction markets might be comparatively worse next to other financial products, “other domains present informational needs that aren’t satisfied simply as a spillover from some other system” and their proliferation has been a clear signal the market values this addition, but hasn’t agreed upon what its final form will look like.

As you’re reading, keep these questions top of mind:

-

What needs changed? (this is intentionally vague)

-

How do these venues scale to billions in monthly volume? (much of the liquidity discussion will hinge around the feasibility of this)

-

Are there any glaring barriers to mass adoption that haven’t been illuminated? (the final section will shine a light on some of the non-consensus views we possess)

Enjoy the report.

Dissecting order books and difficulties in market making

Liquidity is central to any market, and one of the most important topics of this report will be the discussion of market making or liquidity provision across major prediction market platforms, beginning with a look at Polymarket.

It’s stated plainly in the documentation, but every pair of event outcomes on Polymarket is fully collateralized by $1 of USDC on Polymarket, with an on-chain attestation occurring when two sides come to an agreement on the odds. For your information, there are multiple different types of markets you will find on a given prediction market platform.

Baheet dissected the typology of prediction markets in a recent X Article, explaining that the function of a platform depends on its specifications of five different categories: liquidity model, outcome resolution, market types, event creation mechanism, and underlying infrastructure, all of which will be discussed in detail. For now, we’re most interested in his definition of market types as it is foundational information.

The three types of markets you’ll find across platforms are binary markets, multi-outcome markets, and scalar markets.

Basic market making and market formation scenario

A basic example of an individual market seen on Polymarket could be two parties with opposing views on the winner of the 2026 NBA Finals, where the Miami Heat and Golden State Warriors are priced at $0.50 respectively, indicating each of these teams has a 50% chance of winning.

Putting aside the fact this matchup would be highly unlikely, the reality across most prediction markets is that a clear favorite could be priced at $0.47, a runner-up at $0.46, and numerous other candidates priced around $0.01 due to a much lower probability of winning. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll say this market was created a week prior to Game 1 of the NBA Finals, meaning only these two teams are in contention.

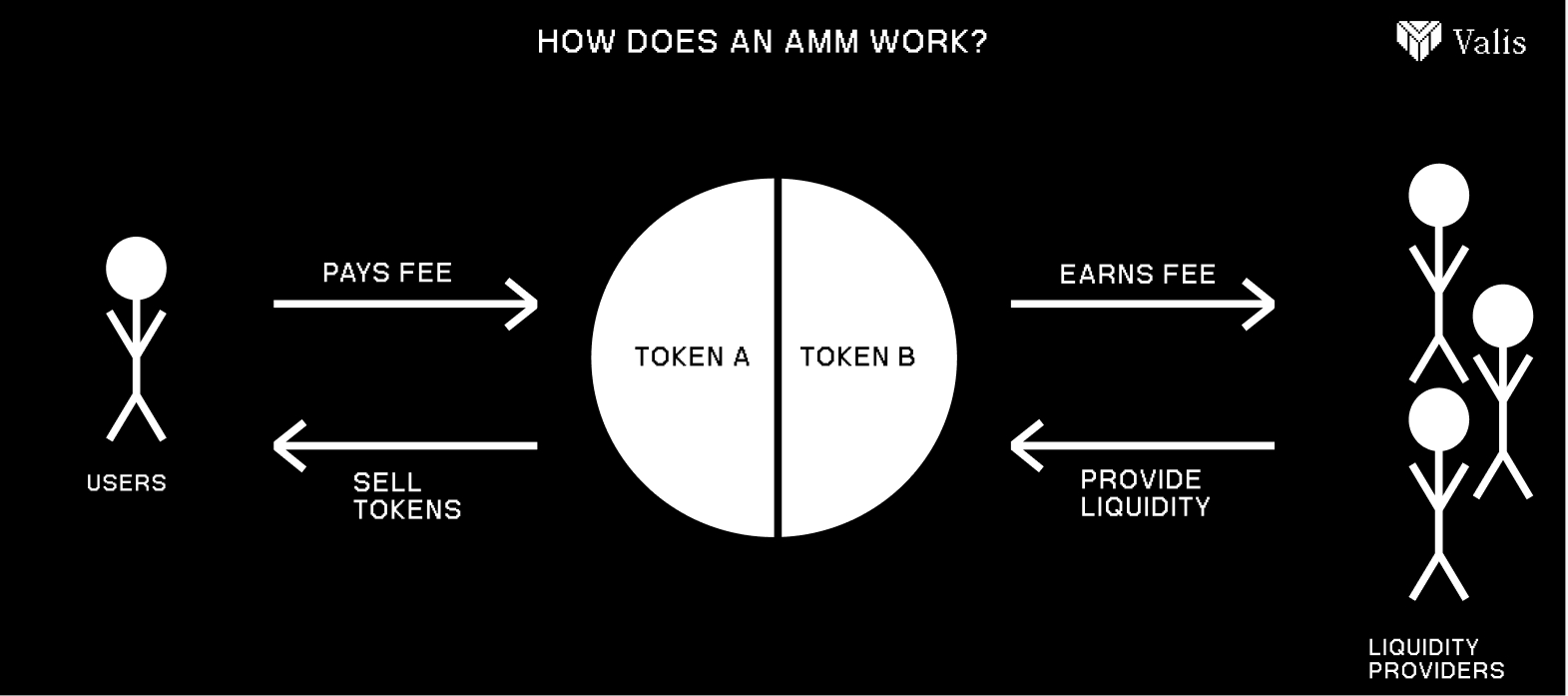

Polymarket used to offer AMM-based liquidity, meaning anyone that wanted to provide liquidity could deposit their USDC into the AMM and back both sides of the market, in this case Miami and Golden State outcome tokens. For context, an AMM is a type of decentralized exchange (DEX) design where smart contracts on a blockchain network manage bids and asks instead of humans directly placing these in an orderbook. AMMs have done wonders for crypto, but Polymarket’s brief stint is emblematic of the shortcomings this technology still faces.

Polymarket grew out of this model as LPs were essentially long on both sides of the market at equal portions, exposing them to inventory risk and led to market making being significantly more frustrating than it should be. Since then they’ve shifted to an order book model, the same type used by Kalshi and countless other exchanges.

A market is formed from an opinion and liquidity comes in afterwards, and regardless of how the liquidity is structured, this is the core foundation that brings event markets to life.

Liquidity must first be seeded by market makers who set the odds themselves. Let’s say a market maker was first and set an order to sell 1,000 Miami YES shares at $0.50 and buy 1,000 Miami YES shares at $0.48. This would be the first liquidity put forth towards the NBA Finals outcome, which a user can then fill. If they decided to fill the ask of our market maker and submit an order for 500 Miami YES shares, they’d effectively become long Miami with 500 shares and our market maker would now be short Miami with 500 shares.

Suppose another market maker comes in and wants to compete, this time submitting a buy order for 1,000 Miami YES shares at $0.49 and a sell order for 1,000 Miami YES shares at $0.51. Our orderbook would now look a bit tighter as additional liquidity has been added, meaning users could purchase another 500 shares from the original market maker at $0.50 before needing to pay $0.51 for the 1,000 shares of the second market maker.

From here, a prediction market operates like any other financial product, in the sense that more buys of the underlying moves the price up, pushing the other asset’s price down in the process. Depending on the outcome and how your inventory, you can either profit a little, profit more, lose a little, or lose it all. If Miami won the championship, anyone holding those shares would see their value increase to $1 each, yet if Miami lost, those shares would trade at $0.

This is the most simple explanation of liquidity provision that will be present in this report, so if you’re still a bit lost, you can read more within Polymarket’s documentation before continuing.

Kalshi’s market creation system is mostly similar as far as market making goes, except the collateralization side does not make use of USDC and is not conducted on blockchain rails.

For a market to be created on Kalshi, it must be launched by the team directly, a creator with exchange approval, or suggested by users for eventual review. Polymarket events can have mutually exclusive outcomes, of which these are all bundled together and collateralized to where $1 covers the entire set. This could be $1 encompassing the odds of five different teams to win the NBA Finals, or five different candidates to win an election.

On Kalshi, each outcome is its own binary (YES or NO) contract, and a market is created by bundling all of these binary contracts together and simply presenting it on the user interface as a single market. This doesn’t affect the end user as the 2028 US Presidential Election markets on Polymarket or Kalshi are displayed the same way, but under the hood, it is very different with a few major distinctions. A multi-outcome market on Kalshi is still functionally the same as a multi-outcome market on Polymarket, just composed under a different set of circumstances.

Because each market on Polymarket is fully collateralized by $1 of USDC, it follows that probabilities must always sum to 100%. Kalshi differs here, as when these binary contracts are stitched together, the probabilities might not sum up to a neat 100%, leading to arbitrage opportunities. This isn’t to say Kalshi’s markets aren’t fully collateralized - they are - but rather they are made up differently from Polymarket, and these structural differences contribute to various strategies used exclusively on Polymarket or exclusively on Kalshi.

Despite these examples making it simple, market making and liquidity provision on these platforms is much more complex and not nearly as black and white as we’ve described it so far.

Some metrics

Before analyzing market making dynamics, let’s observe more general metrics like volume, open interest, transaction count (where applicable), and DAUs to paint a picture of where these platforms are in the race for more users.

Of their $34 billion in volume inception, ~79% of this comes from Polymarket and ~21% from Kalshi. There hasn’t been a visible struggle between the two to attract market makers or retain liquidity, though as we’ll cover shortly, some of Kalshi’s recent tactics have put pressure on Polymarket’s once sizable lead in market share. More recently, Kalshi has seen its market share looking at weekly notional volume via Dune increase from 8% in January 2025 to just over 62% in September 2025.

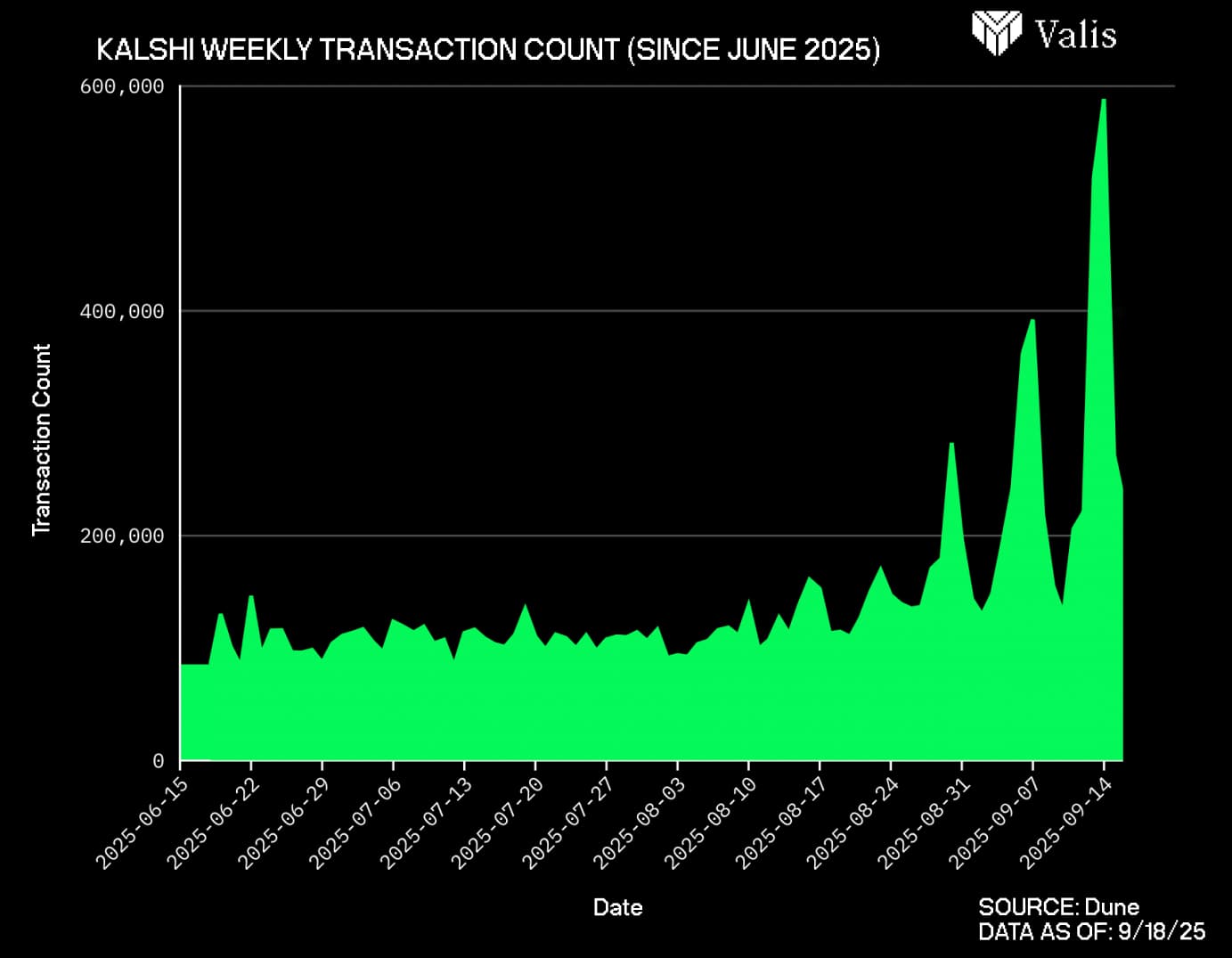

Polymarket’s user count is visible due to it being a blockchain-based application, while Kalshi is a centralized application, meaning transaction count is a better metric for getting to the bottom of actual usage. Polymarket is sitting at 61 million cumulative transactions since inception compared to Kalshi’s 30 million, according to Dune. Polymarket has 2x the amount of transactions than Kalshi due to Polymarket having been around longer, while Kalshi has only entered the discussion more seriously relatively recently.

This isn’t discounting Kalshi, as we must note despite Kalshi lagging in cumulative transaction count, their recent growth has far outpaced Polymarket.

Going back three months (to June 1st 2025), Polymarket has averaged around 147,000 daily transactions, while Kalshi has seen an average of 142,000 - an improvement from their previous 2024 average of 24,000.

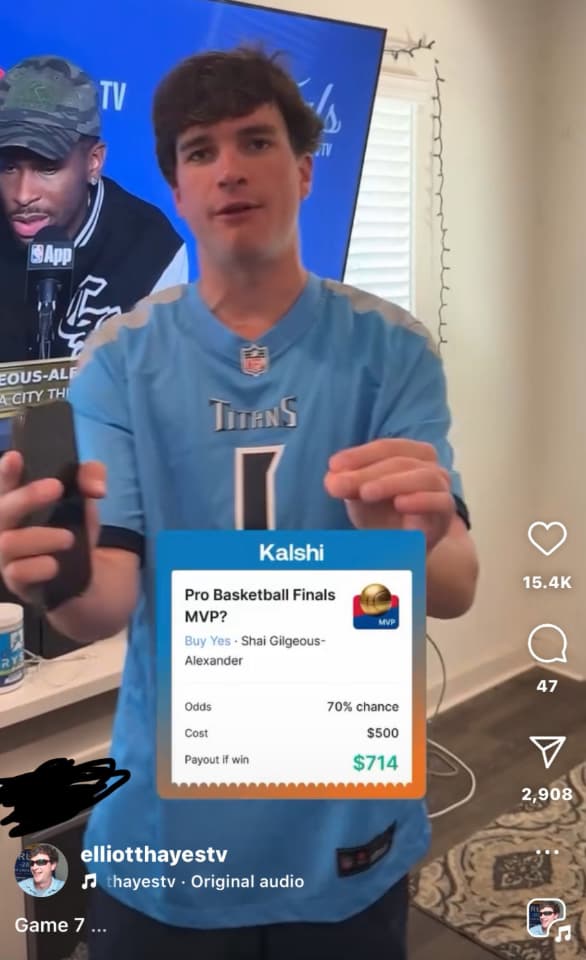

But if we look at more recent data and shift our focus to September exclusively, Kalshi has averaged 260,000 transactions through the first eighteen days of the month - Polymarket with 161,000 daily transactions - largely attributable to their prioritization of sports-related markets and growing sports-first mindset.

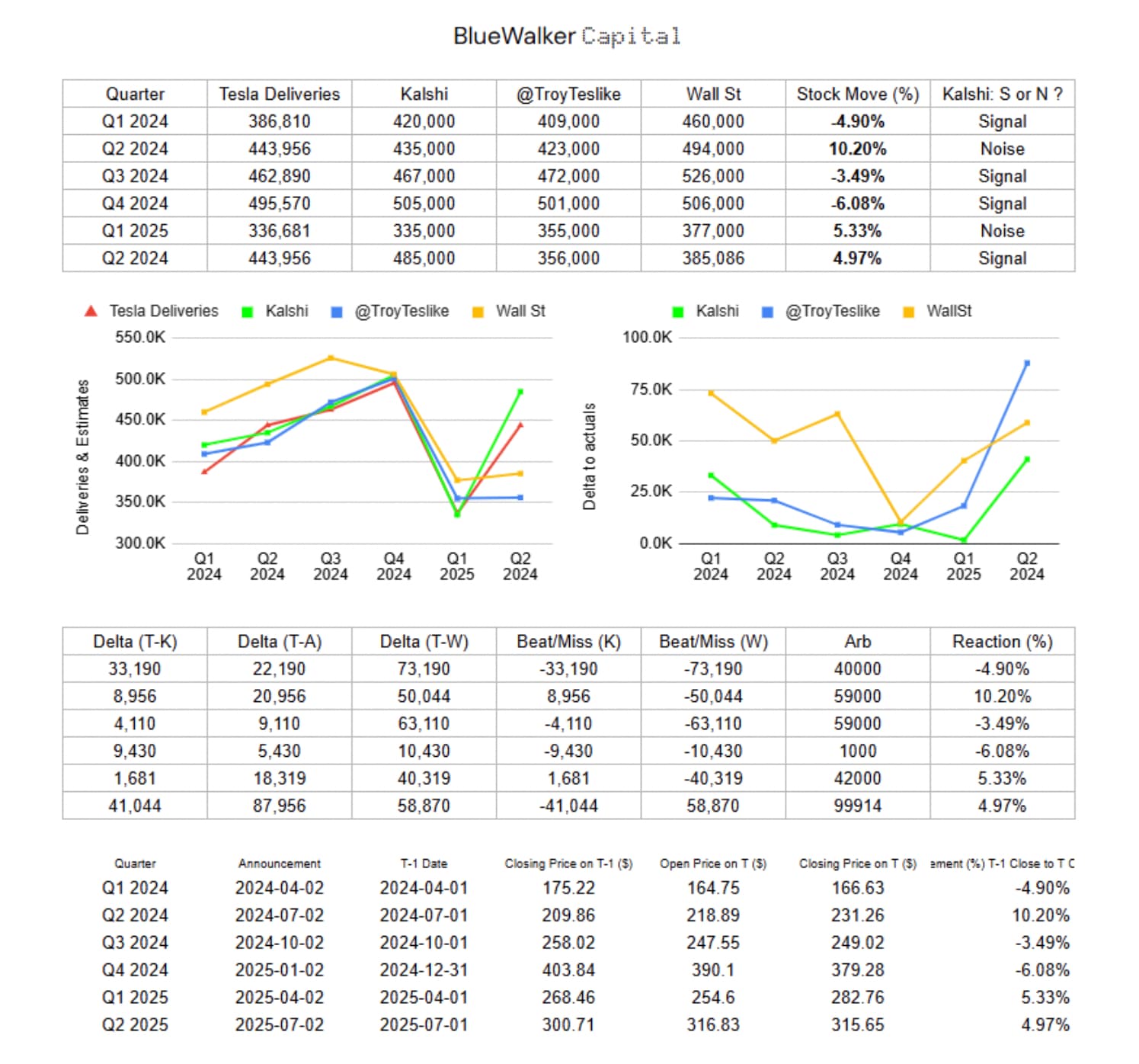

We’ve discussed that sports betting is a massive industry and is only continuing to grow, but it’s becoming apparent that this growth needs to be examined in light of Kalshi’s massive push into sportsbook territory and the implications this has for these two industries.

DraftKings is one of the largest online sportsbooks in the United States, and just happens to be a publicly traded company, giving us insight into their historical revenue.

All of this data was pulled from DraftKings’ investor relations pages , meaning we were unable to access more recent data since the start of the 2025-2026 NFL season, as this won’t be public until Q3. Regardless, the numbers show a potential trajectory or more realistic growth model for Kalshi, should it continue encroaching on traditional sportsbooks’ volume and users.

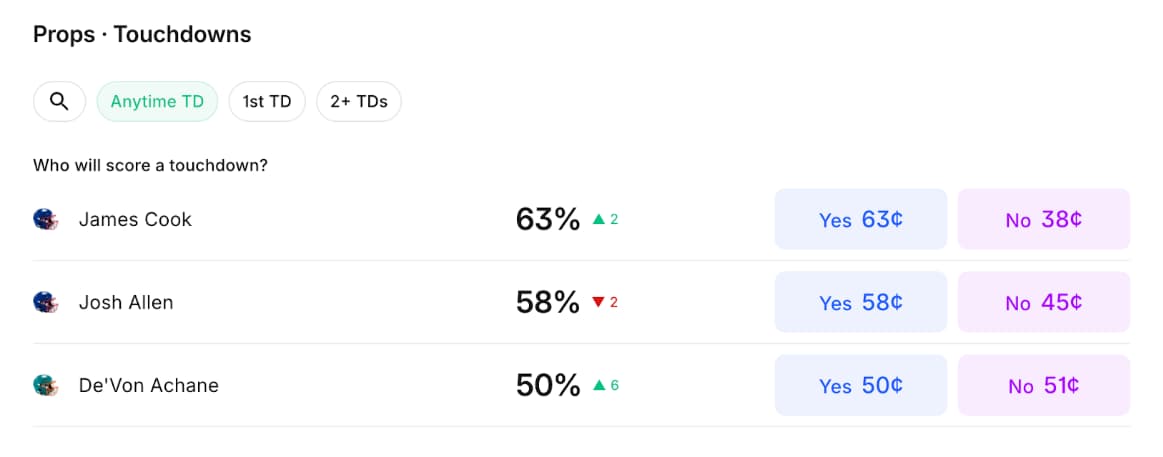

Regarding the encroaching, Kalshi has been quite active, with Adhi Rajaprabhakaran reporting that Kalshi submitted a new filing to the CFTC over a month ago on August 18th, requesting explicit permission to list player props and point spreads, a step beyond more traditional offerings of moneylines or futures contracts.

Kalshi’s hoop dreams

It’s easy to assume Kalshi is quite aware of the growing dominance of parlays and prop bets amongst sportsbooks, making a filing like this a no-brainer, and with roughly 80% or more of Kalshi’s weekly volume coming from sports alone, they are doing quite well. Here’s a screenshot of the September 18th matchup between the Miami Dolphins and the Buffalo Bills, showing live player props:

One of the more underrated benefits of using Kalshi as opposed to another sportsbook is the lack of any cashout penalties or fees. Closing out of a position on DraftKings might lose you 25-30% of your bet, especially if the game has already started. Cashing out on Kalshi depends on other factors like liquidity, current prices, and potential short term swings, but is significantly more frictionless than any alternatives.

We could write pages and pages regarding Kalshi’s push across the US to further sink its teeth into sports betting, but the decision to do so is best understood through this anecdote in the same post referenced above:

“Sportsbooks' entire revenue model rests on high-vig markets and the ability to profile and limit sharp players.”

It’s common knowledge that if someone becomes too good at sports betting, they’re likely to get kicked off of the platform. This has led to the creation of many different workarounds over the years - quite an interesting rabbit hole - but is best highlighted by the counter to this extractive model: Kalshi and Polymarket have no incentive to ban their top traders, as they don’t operate as “the house.”

This is a rabbit hole in and of itself, considering a recent comment made by Kalshi’s Head of Corporate Development regarding their internal market making team (known as Kalshi Trading), particularly that “Market makers, including KT, compete for flow in an open, transparent and fair marketplace, and set their own prices as to what they are willing to pay for a contract, but are not able to dictate the broader market beyond that.”

It isn’t our place to confirm or deny whether KT or any other market makers receive preferential treatment, as this type of data isn’t accessible, but this conflict of interest has been brought to attention by many and its implications are best summarized here:

“It’s one thing for Kalshi to claim that market makers cannot influence the market despite their fee rebates, it’s far more egregious to make said claim while simultaneously wielding economic power to reduce competitive pricing in those same markets.”

It could be assumed that sharps would slowly gravitate towards Kalshi instead of risking their livelihood on traditional sportsbooks, especially if market makers are receiving more favorable rebates or kickbacks in any form.

But has this already begun to happen? It’s tough to say.

Dustin Gouker of The Closing Line posted a weekend data dump on September 8th, highlighting Kalshi’s $300 million of volume, with a ridiculous 96% of that volume coming from sports, and 84% of that from football (NFL) alone. That isn’t just impressive for a prediction markets venue, but arguably on par with mid-tier sportsbooks.

This is not to say that Kalshi is immediately in contention with a name like DraftKings or FanDuel, or that all of these incumbents’ customers will move to Kalshi, but it’s hard to ignore Kalshi’s more favorable regulatory positioning with the CFTC which lets them market their product in all fifty states.

Considering sports betting is not legal in all fifty states - and the states that offer these services see a significant amount of annual revenue from this - it’s not hard to imagine why seven pro-gambling states have issued cease-and-desist orders to Kalshi in recent weeks. Benjamin Sturisky explained how Kalshi is able to skirt regulators and offer their services without repercussion:

“Additionally, because Kalshi is a third-party provider that does not have stake in the event outcome, they are recognized as a peer-to-peer platform and not a bookmaker.”

Kalshi is moving fast and breaking things.

Another angle here is whether or not analysts could use Kalshi activity as a proxy for predicting DraftKings or FanDuel’s quarterly earnings. This is more than likely an original idea that you can only get on Valis Research. But we aren’t exaggerating, and believe there is some truth to this whacky proposal.

Incentivizing more liquidity inch-by-inch

We discussed that Polymarket and Kalshi have different strategies of seeding liquidity across new markets, but these platforms also differ in how market maker presence is maintained throughout a market’s life cycle, and their incentive structures are most emblematic of this.

We can examine the most basic level of competition through available data and take a closer look at liquidity incentives and targeted incentive distribution as these are the two most relevant drivers for incentivizing volume on both Kalshi and Polymarket.

Regardless of the market, there must be an incentive to participate, whether you are a market maker, a retail trader, or an institution taking a position on something. As discussed, market making zero-sum prediction markets is a difficult game and has frequently been brought up as the most important bridge to cross prior to the introduction of more users, more institutional trading activity, and of course, more volume.

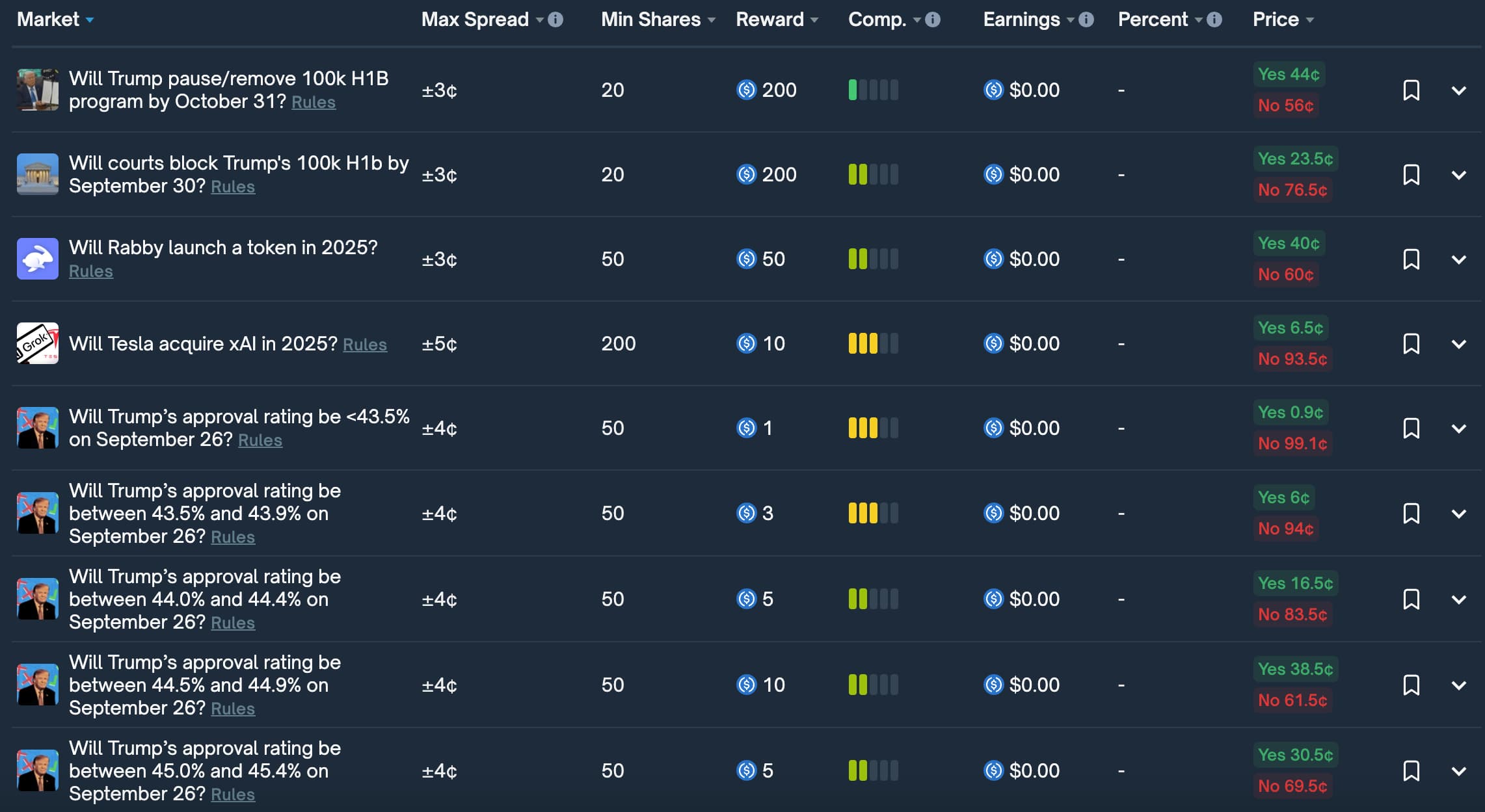

Polymarket may have recently created this liquidity incentives dashboard, but it stands out as a nice initiative to draw in more amateur market makers with specific descriptions around what’s required of them and what’s exchanged in return.

The dashboard lists max allowable spread, USDC reward, the competitiveness of each individual market, and the existing prices. This is a good start and it’s clear that the markets being incentivized are clearly going to be hot at some point, but struggling to get off the floor and all trading with very low liquidity. From a very high level, here’s a basic description of how Polymarket determines liquidity rewards:

-

Closer to average price = more earnings

-

Reward amount depends on how “helpful” your orders are to others, in terms of size and pricing

-

More competitive the limit orders are, more you can make

-

Paid daily based on how much your orders add to the market

The actual formulas of these platforms will be covered very soon, but keep in mind it isn’t possible to track Kalshi’s market incentivization, though we can potentially extrapolate and come up with a mental model of what markets would be most incentivized if we ran Kalshi.

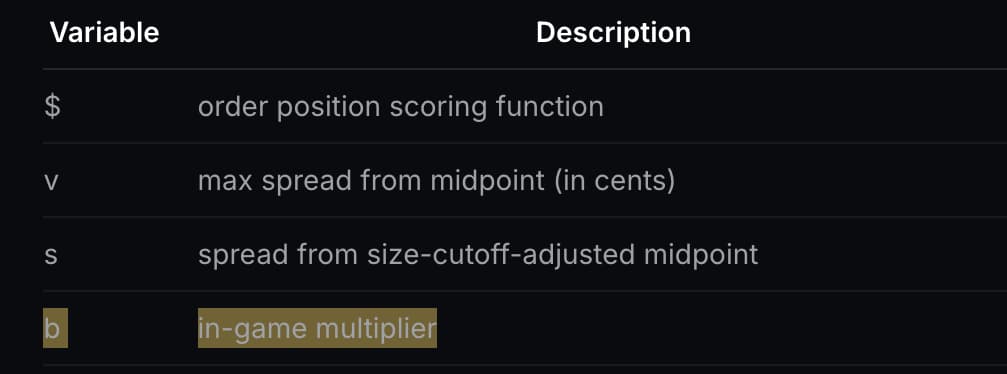

Looking at Polymarket’s developer docs, there’s a list of variables and their accompanying function - most interesting being the b-value and its role as an in-game multiplier.

We know that liquidity rewards can be juiced by either of these platforms, but it’s tough to say when this might be happening and what markets it’s occurring in. Despite this information gap, we can observe these platforms’ open interest metrics and come to a conclusion that neither has seriously juiced rewards enough to ice out their competitor.

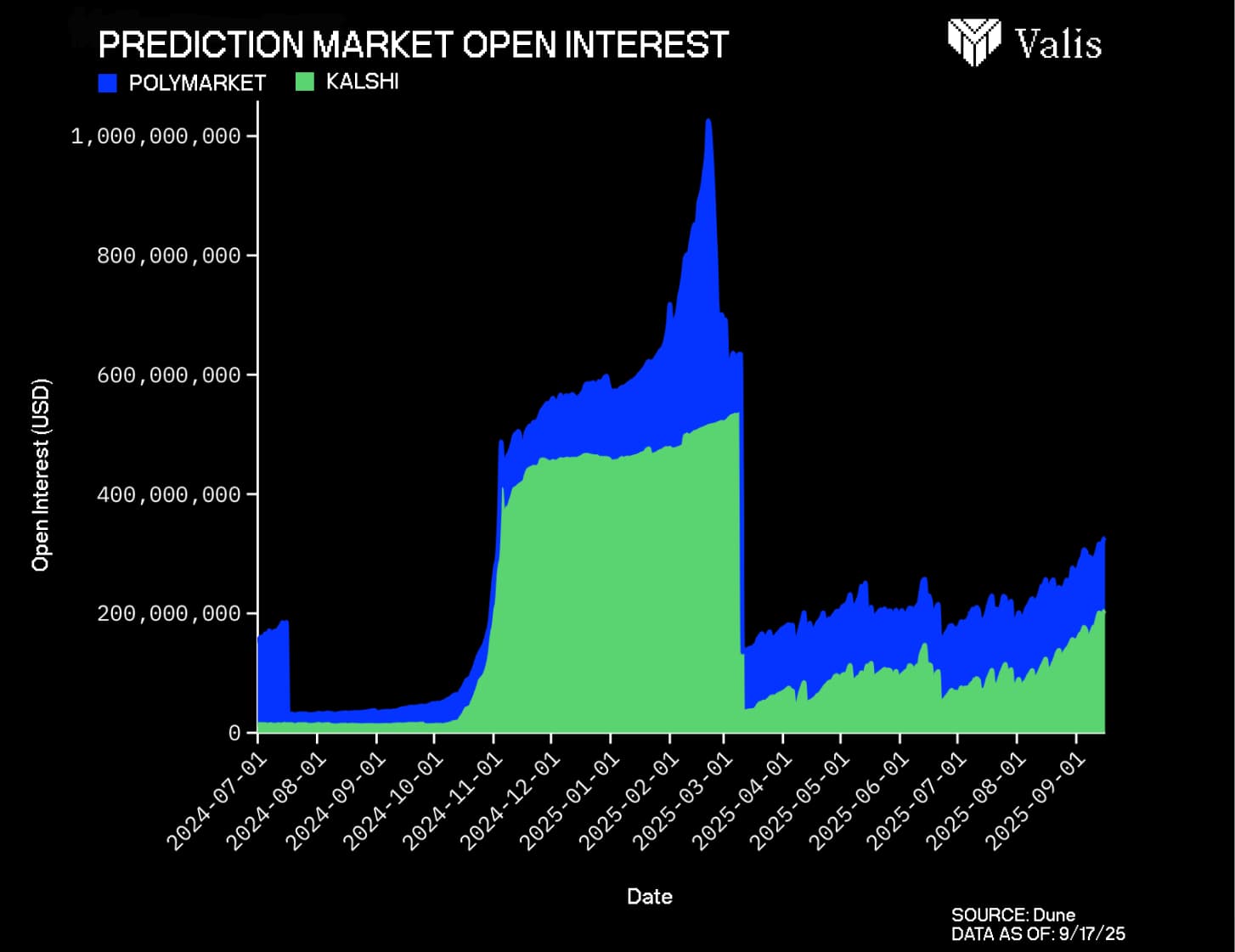

As of September 17th, Polymarket and Kalshi had over $370 million of open interest across all of their markets, a sharp dropoff from the Q4 2024 peak of over $1 billion combined open interest, yet visibly stronger since the start of this year:

It should be noted that despite open interest down over 60%, this hasn’t stopped volume from approaching all-time highs: how does that work? In the case of the US Presidential Election, many were simply holding positions in Trump or Harris shares, rather than trading more short term markets back and forth. Volume was obviously high as well, but we’re seeing a different dynamic now where more markets are being traded and dispersion is common given nothing can compete with the significance of a presidential election outcome.

This distribution of open interest and consistent lead held by political markets can be explained by the obviously lofty implications tied to US elections, but also due to how widespread politically charged content is on social media like X, a platform that Polymarket and Kalshi frequently make use of for advertisements and news releases.

There’s an additional case to be made that political prediction markets are comparatively easier to market make due to the vast amounts of data available online, though this can’t be answered without speaking to market makers directly.

Not all liquidity is equal, and just because a platform has over $100 million of open interest, does not mean this platform has uniform liquidity, though this is more obvious with an example.

The 2024 US Presidential Election was - across all platforms - the most liquid and largest volume driver and has remained the peak of prediction market activity. At one time, there was over $150 million of open interest on this one market, representing a >50% market share considering Polymarket’s $300 million of OI as of October 29th last year.

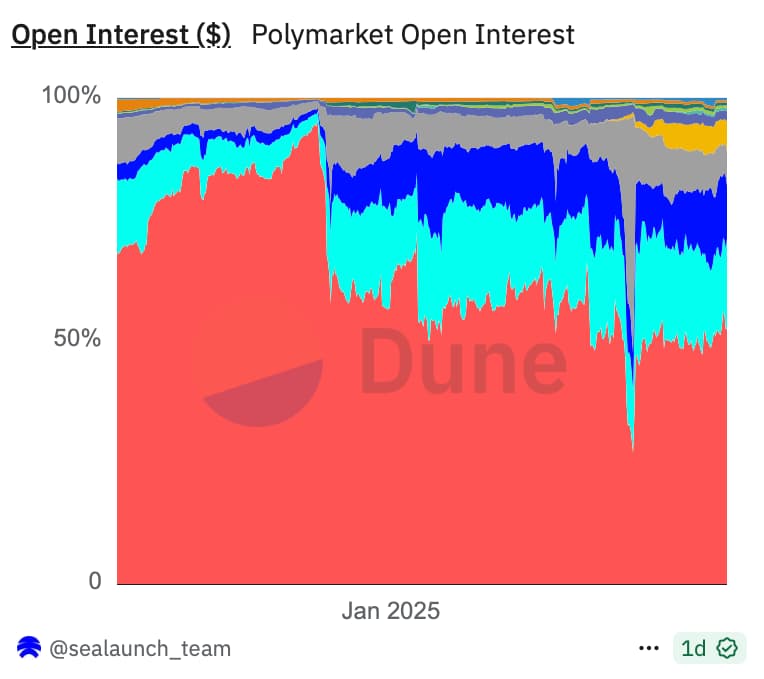

Here’s what Polymarket’s open interest by category looks like today, referencing the dashboard created by @sealaunch_:

We see open interest is spread out across categories like crypto (neon blue), other (gray), business (light purple), sports (dark blue), and politics (red), but this massive skew towards a single market is not the norm. Even with politics maintaining a roughly 50% share of Polymarket’s open interest, there’s a healthy distribution amongst categories that aren’t sports.

How might these platforms go about incentivizing liquidity for non-political markets, or categories that are potentially more unpredictable and long-tail by nature?

Solutions to solving liquidity and why they’re necessary

Yoshi wrote a short article that offers up five unique ways of solving the liquidity problem of prediction markets, and the most interesting part is that each of these ideas targets a different side of the prediction market space. There’s a proposal to onboard more futures & options (F&O) market makers, a proposal to introduce a bonding curve similar to pump dot fun’s seeding of memecoin liquidity for long-tail prediction markets, and other basic proposals that seem pretty realistic and achievable, even in the short term.

You might be wondering why this is even a discussion: if the mechanisms for seeding liquidity or improving the distribution of liquidity are so obvious, why isn’t it being done?

This is a great question but it fails to recognize the state that Polymarket and Kalshi find themselves in. Remember how over 90% of Kalshi’s September 2025 volume has originated from sports? If you’re a platform that’s seen a significant increase in volume from a specific category, maybe you’re more inclined to incentivize this in the future.

Dustin Gouker posted on X that Kalshi is hiring two sports positions, one requiring “Extensive experience with sportsbooks – understanding how sportsbooks operate, common market types, settlement procedures, and the edge cases that arise in sports market operations” giving more credibility this is a direction they’re going in.

After all, if sports betting has done over $500 billion of volume since its legalization in the US and remains a go-to hobby for young men, why not go head-to-head with some of the largest sportsbooks out there?

You need market makers to not only feel compensated for their work - very difficult work considering these are zero-sum payout structures - but compensated to a degree they are unwilling to migrate their operations to another platform or competitor. If you think about it from a risk/reward perspective, incentives should be quite high.

Reducible Errors says it best:

“With binaries, imagine the market is trading around 50%. If you're very short, you lose a lot if it settles to yes, and vice versa. But there's nothing you can do to reduce risk. All you can do is hope.”

Simply offering more incentives than the other guy is one way of maintaining liquidity, but keeping them around given the risks involved is more important, especially considering this undeniable reality of adverse selection.

A necessary counter to this comes from the fact that sports books are a market maker’s wet dream, given the allure of uninformed retail flow coupled with more predatory incentive structures present on sports books. It would be foolish to assume market makers wouldn’t accept a bit of inventory risk in exchange for massively uninformed retail flow (and favorable fee structures or rebates) on a platform like Polymarket or Kalshi.

Yoshi’s suggestion to onboard more F&O market makers is probably the clearest solution in the short term for sticky liquidity, due to the similarities in payout structure, but it’s also necessary considering the risk a non-professional liquidity provider might face in any given prediction market. With these MMs having a history of managing inventory risk and the skill it takes to accurately model volatility in a new market, their presence would potentially lead to tighter spreads but a level of sophistication that is yet to become widespread across these platforms./p>

This makes sense on paper but it’s worth noting that even if these MMs entered prediction market trading with the knowledge of other sectors, this wouldn’t translate 1:1 given the difficulties in hedging binary prediction market outcomes. F&O market makers can make use of countless strategies, tools, and feats of financial engineering to hedge anything, but doing this in the existing prediction markets space is quite challenging or nearly impossible.

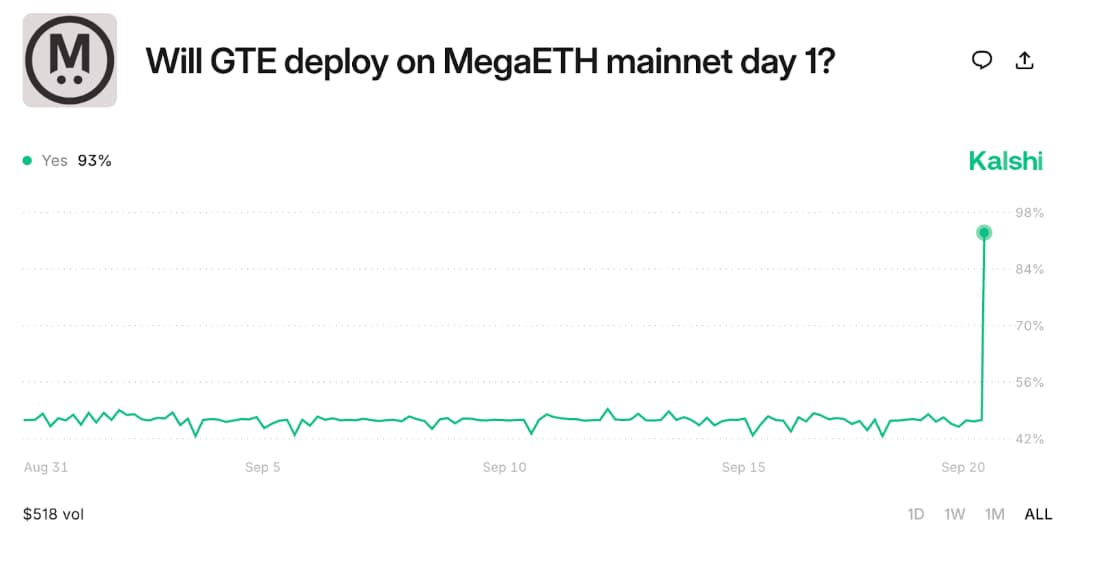

Among the other liquidity proposals, Yoshi noted how bonding curves - made popular by pump.fun and their memecoin liquidity bootstrapping model - are a potential route for any platform looking to incentivize long-tail liquidity specifically. We noted how Polymarket began with an AMM model for market bootstrapping, before shifting to a primarily orderbook-based system: what if a subset of Polymarket’s more niche or risky market creation utilized a bonding curve like pump.fun?

This is an understandable solution given the obvious market making risk for any long-tail event (see: will aliens visit Earth by 2030?) but also benefits the platform as a whole, should more speculative-minded individuals wish to see larger potential payouts on Polymarket.

Referencing Adjacent again:

“When a market is new, niche, small and low liquidity often utilizing an AMM curve can be very helpful. Liquidity providers generally provide passive liquidity to an AMM allowing traders to always have a price to sell into”

A really good example of this is the below market, in which approximately $241 were used to push the price of the contracts of this event from ~0.4 to ~0.9. Pretty interesting. For the unaware, refer to this tweet from the GTE team regarding their departure from MegaETH.

A smaller proposal offered was the potential for resolution-based incentives, or market maker incentives that only distribute (or vest) after the resolution of a given market. This would disincentivize wash trading and allow for a platform to incentivize early liquidity (via scaling reward distribution asymmetrically towards the start of a market), but would require manual oversight when it comes to which markets are best fit for this.

On the topic of wash trading or minimizing market maker shenanigans, Kalshi somewhat recently introduced a new incentive structure meant to encourage deeper, more consistent liquidity across all of its markets, a step in the right direction for solving this liquidity problem.

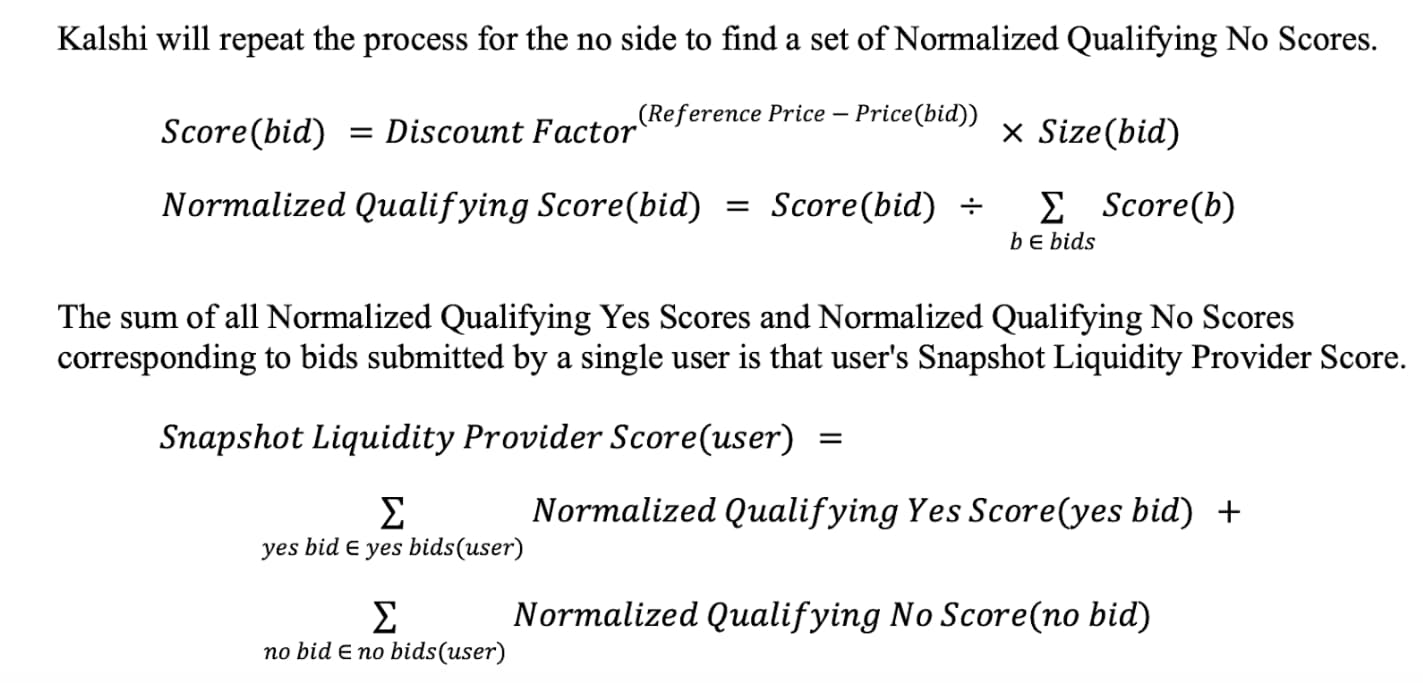

Kalshi’s new plan for liquidity defines three parameters, set in place for each market they designate as eligible. These are target size, discount factor, and time-period reward.

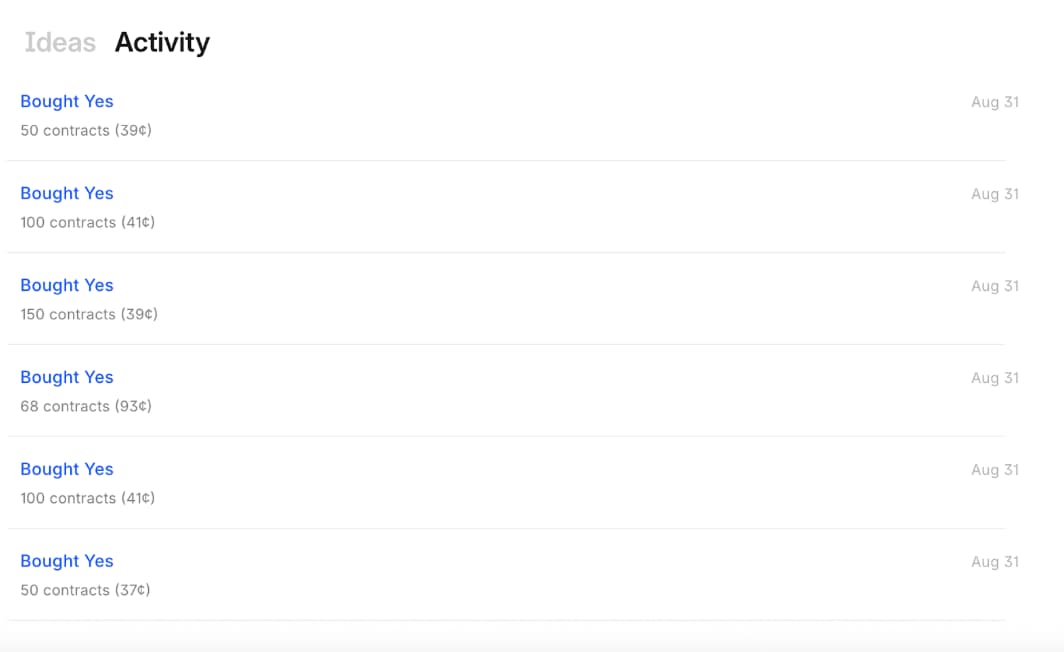

Using an example from Adhi, an aspiring market maker might offer up an order for 1,000 contracts on a market with a discount factor of 0.9 and a reward pool of $100.

These 1,000 contracts might be split between three separate price points (best bid, one cent away, two cents away) representing three unique payouts structures for this order. The math is pretty simple on paper, with a score calculated by multiplying the size by the discount factor taken to the power of distance from the best bid.

This simple calculation measures the reward rate for Kalshi’s market makers, explicitly prioritizing tighter liquidity and mitigating mercenary market makers by running a second-by-second snapshot.

It’s understandable that Kalshi would want to reward stickier liquidity, but what’s important is this revision makes it difficult to ascertain what systems are or aren’t in place at Kalshi, and their centralized nature makes it nearly impossible to get a glimpse into what’s going on behind the scenes.

The rumors of zero fees or rebates for select market makers has circulated more frequently as of late, though exact details of this are uncertain. SIG (Susquehanna International Group) was the first institutional market maker onboarded to Kalshi (in April 2024) and we aren’t here to debate the business acumen of these teams, but it would be ridiculous to assume SIG didn’t agree to this without some form of preferential treatment. If this sounds exclamatory, just reference all of the replies to this post as a sentiment check-in.

Even though as we know frontrunning is a big problem in this type of market, Polymarket and Kalshi both heavily incentivize market makers to provide two-sided liquidity, heavily penalizing those who don’t follow this rule.

Kalshi incentivizes market makers to provide two sided liquidity by soft slashing those who don’t quote one side. If a market maker decides to quote only on one side, the other side of the equation would be essentially zero’d out, giving a big incentive to provide liquidity on both sides of the orderbook. According to Kalshi’s docs market makers are only able to earn liquidity between $0.03 and $0.97. This makes sense as it disincentivizes gaming the market towards extreme prices.

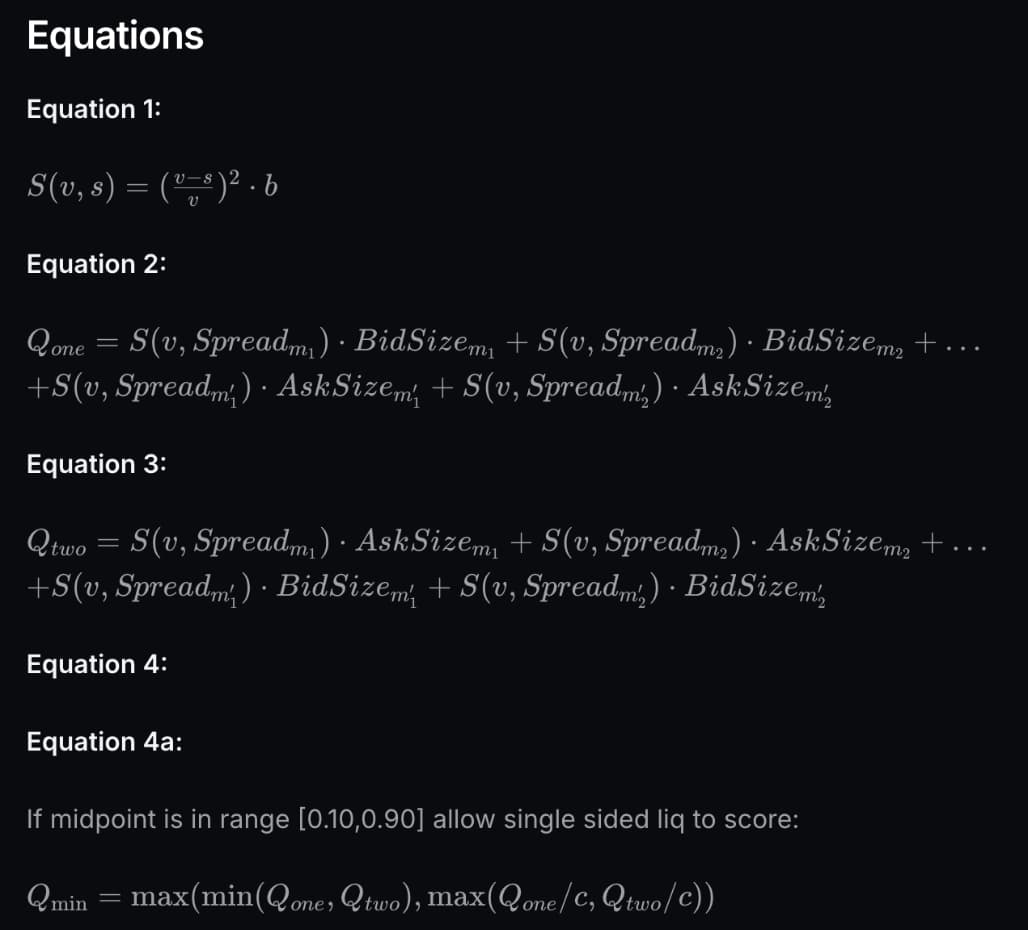

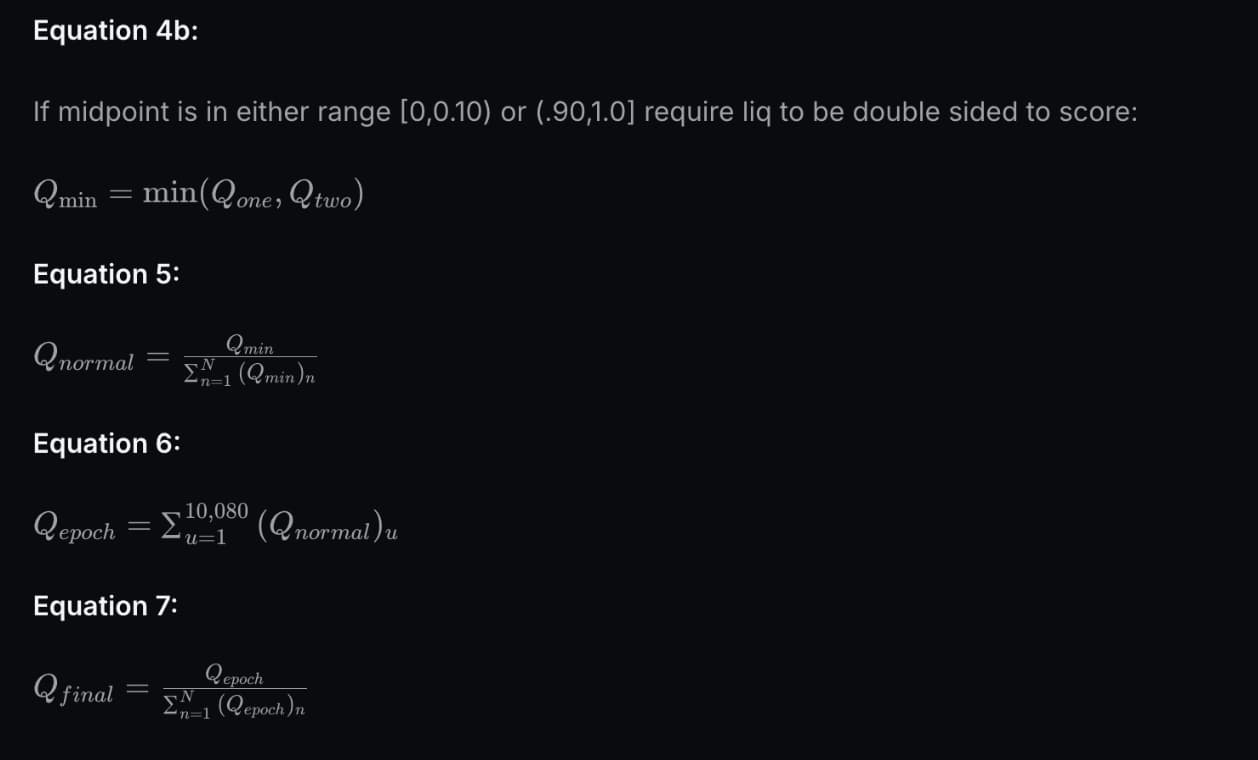

Polymarket is even harsher at penalizing one sided liquidity. If you look at the equations below, providing one sided liquidity means that you’ll essentially get whatever points you accrued divided by 0.3333. Furthermore, you can only provide one sided liquidity when the contracts are trading between [0.1, 0.9] if you want to earn points outside that range, you have to provide two sided liquidity.

Conclusion of this is that Polymarket is much harsher at penalizing one sided liquidity, which is interesting because at the same time its platform is much more prone to insider trading because of lack of KYC. AKA, they should be more lenient with one sided liquidity provisioners as the chances of getting front runned by insiders are significantly higher on Polymarket vs Kalshi.

Quoting Adhi in the same post as above:

“The exchange doesn’t have to do the work of finding and hiring a trader who is good at both. They can also just pick and choose which markets need more liquidity at will. Polymarket has enjoyed the perks of this system for years now.”

This is a shift for Kalshi, as their previous model consisted of fee rebates to incentivize market makers, yet this filing (PDF, via the CFTC portal) explains how the incentive system’s restructuring priorities volume and liquidity.

This document also confirms some type of axing of the previous rebate program but doesn’t give details, only stating: “For the avoidance of doubt, Kalshi hereby notifies the CFTC that Kalshi’s volume incentive program filed in October 2024, and Kalshi’s fee rebate program filed in January 2025, did not go into effect and are hereby terminated.”

Liquidity incentivization and the multiplier

The in-game multiplier appears to have been discontinued for a more discrete liquidity incentives program. AKA round numbers, probably to simplify liquidity provisioning for market makers. Only 32.3% of active markets have liquidity incentives.

Polymarket is spending approximately ~5m on their liquidity incentives program. Around 90.5% of markets being incentivized have 5 dollars of less a day in incentives. On the sportsbook, most markets have close to zero liquidity incentives (The median is 1).

However, some markets related to teams with high likelihood of making the superbowl final are being heavily incentivized with around $400 in liquidity/day. This indicates that Polymarket isn’t really trying to ‘vamp’ or compete with Kalshi for all sportsbook plays but only for the ones with the deepest liquidity (Super Bowl final). Probably because of regulations, Kalshi cannot really offer ‘Will X beat EPS this quarter’ because it’s too similar to a financial product. However, this is a pretty interesting market for Polymarket and is one they’re incentivizing pretty heavily in liquidity.

These markets open up close to the expiry date and sometimes can attract significant volume. COST is the most incentivized market right now. 69.5% of the markets with $100 or more in liquidity incentives per day are related to politics, it seems like Polymarket is more interested in competing for culturally relevant/politics rather than sports, which is the game that Kalshi is playing.

According to Kalshi’s API, currently 35 markets are being offered liquidity incentives, with all but two of these being sports markets. Kalshi has spent $8.75 million since inception on incentives and is averaging about $35,000 per day, nearly 2x the average daily spend of Polymarket. Quick aside, this site lists 37 active markets being incentivized, though overlap is significant so take both with a grain of salt.

Kalshi's market making docs explicitly mention benefits "including but not limited to financial benefits, reduced fees, differing position limits, and enhanced access" which was already known, but whether or not certain market makers get more preferential treatment than others is a different story.

Fortunately, we can more easily determine what Polymarket is doing.

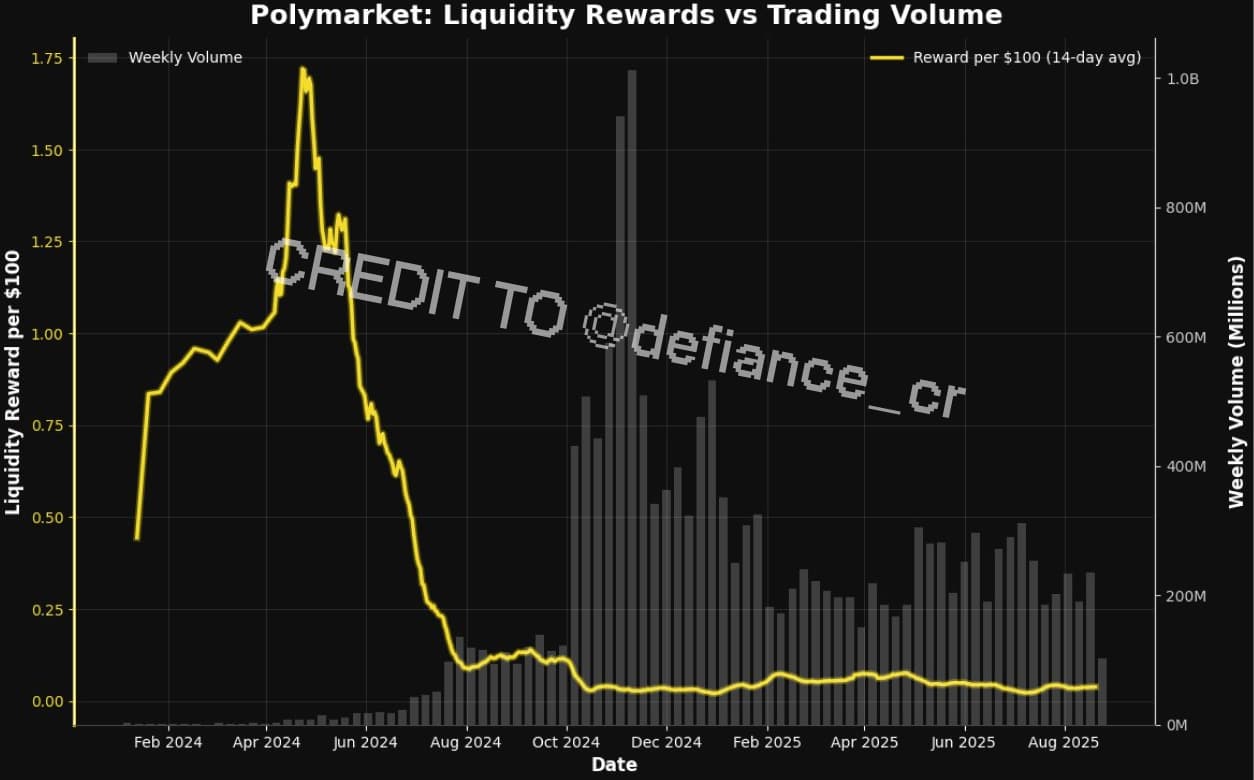

There was a brief phase at the beginning of 2024 where Polymarket was paying out $1.7 per $100 of volume to its market makers highlighted by @defiance_cr here before returning to a more reasonable $0.025 per $100. It would be reasonable to assume this significantly boosted the platform’s volumes, as everyone appreciates a bit of extra money, but actually, this didn’t do much to grow their volumes, as you can see from the graphic below:

This chart shows Polymarket’s volumes actually grew significantly, after they’d shifted back to $0.025 per $100 of rewards, meaning LPs were relatively indifferent or potentially unaware of the significant earnings boost.

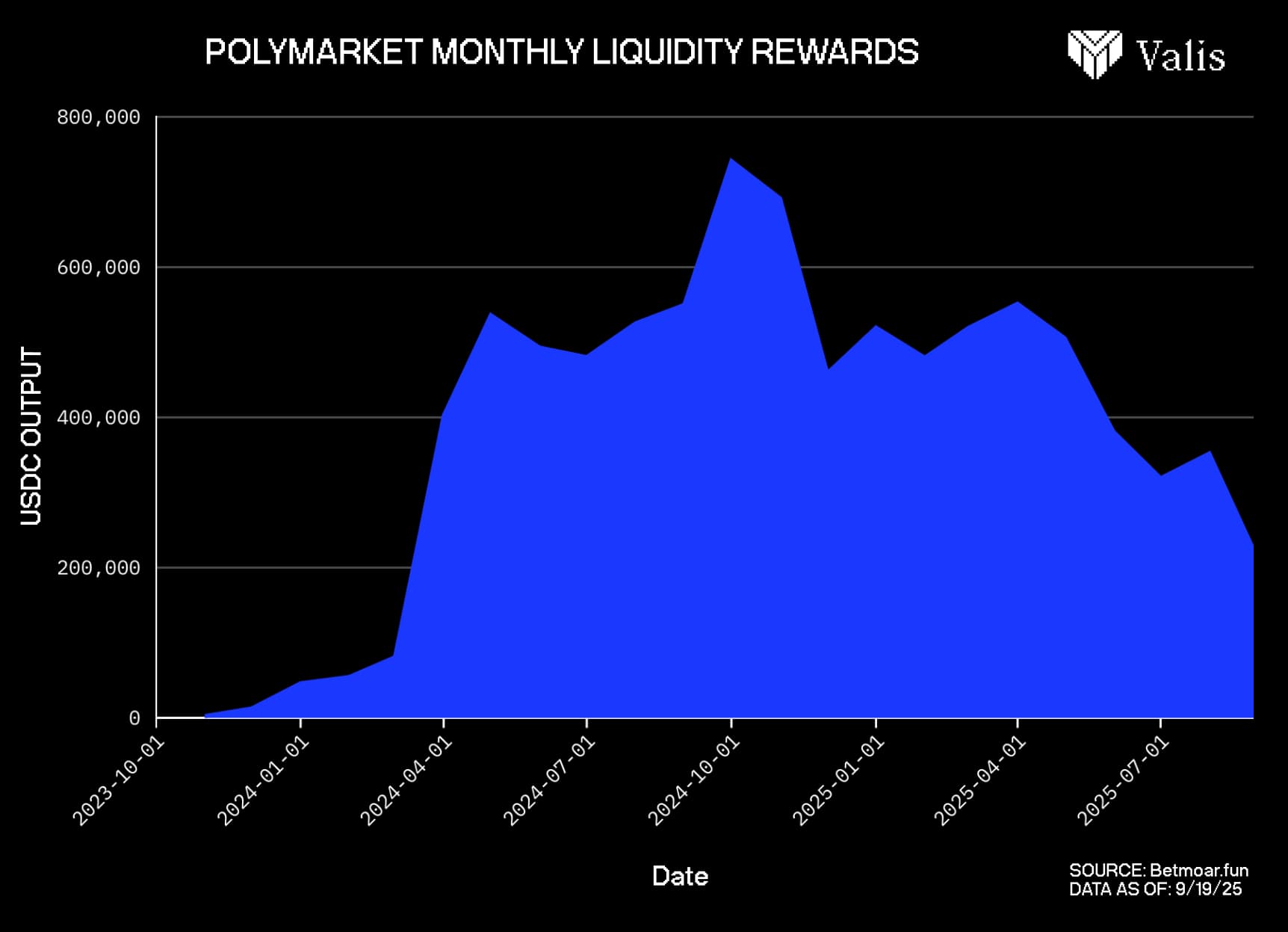

According to betmoar.fun, Polymarket has paid out close to $10 million in liquidity rewards since inception, and we’ve established that Kalshi’s data is opaque, though it can be assumed they’ve paid out a similar amount. Keep in mind that when we say that $10 million has been paid out, this comes entirely in the form of USDC (or other USD-backed stablecoins), not token rewards as neither platform has issued a token.

There is a short bit of analysis from Lucas of Adjacent that digs into the benefits should Polymarket launch a token, though we’ll save this brief discussion for later, but it’s worth mentioning that the launch of a token for Polymarket would significantly alter the race between them and Kalshi - stay tuned.

Regarding Kalshi - and we can’t say this is conclusive or what’s definitively occurring - it’s possible that reward distribution under the hood has remained unchanged, or only slightly increased, but more than anything might be comprised of a more favorable set of conditions for market makers, specifically these third parties or external trading partners like SIG.

But the liquidity problem goes deeper than that and concerns the immediate onboarding of more institutional market makers.

Taking the definition straight from Wikipedia, “adverse selection is a market situation where asymmetric information results in a party taking advantage of undisclosed information to benefit more from a contract or trade.”

Why should you be concerned with adverse selection?

If you’re a US citizen looking to trade prediction markets and are unsure whether to use Polymarket or Kalshi, you can rest assured knowing the question has already been answered for you. As of writing this, the only way to use Polymarket in the US is by working around jurisdictional restraints and using a VPN, leaving you with Kalshi.

This isn't by design, as it isn’t like Polymarket decided on their own volition to not offer its product to over 300 million Americans, but a result of Polymarket not yet being in favor with the CFTC though actively working on it.

Kalshi gained its DCM (Designated Contract Market) status in 2020 and won a federal court decision allowing it to offer event contracts in the United States. Regulation and legal speak is boring but it plays quite an important role in many of the other topics discussed, especially market making.

Because of its current legal status, Polymarket has been unable to sign contracts or form agreements with external / third party market makers like Kalshi has: most notably their partnership with SIG, made public in April of last year.

Polymarket has also been unable to efficiently rid itself of any potential insider traders and adverse selection taking place within its markets, something Kalshi could theoretically do given KYC requirements. Due to these obstacles in its way, Polymarket hasn’t marketed itself in a way that Kalshi has, meaning their inability to defend against toxic flow has hindered the crucial process of onboarding more sophisticated market makers, those that are probably unwilling to subject themselves to even the possibility of trading in an environment with toxic flow.

Our main takeaway here is that the blanket statement “market making prediction markets is bad” might be true, but it’s rarely discussed as an immediate concern to these platforms’ growth. Despite the obvious challenges, it’s these irregularities and quirks of prediction markets that have propelled them to their current status, indicating there is potentially significant value in solving these problems as a third party or directly within organizations like Polymarket and Kalshi.

Questioning parlays and leverage

Discussing liquidity and the rabbit hole of market making was very important, as without it, we’d have no basis for arguing against the feasibility of parlays and leverage. And yes, they are very much really difficult to solve at scale given these current liquidity limitations.

Parlays are quite popular and have quickly become a major source of traditional sportsbooks’ revenue. Quarterly earnings reports don’t explicitly reveal what percentage of FanDuel or DraftKings’ revenue is coming from parlays and prop bets, but a 2023 blog via PGA Tour claimed that parlays represented nearly 70% of all NFL and NBA bets placed on FanDuel.

Anecdotally, almost everyone prefers the payout structure and lottery-type outcomes associated with a parlay, and there is a small but growing ecosystem of content creators across social media that offer parlay advice, specific bet setups, and other information targeting this bucket of sportsbook users.

Sportsbooks make it quite easy to build parlays within the app, offering specialized tooling that pools together disparate bets into an n leg parlay without the need to manually calculate odds. All parlays are different and ridiculous 10+ leg parlay posts are widespread across platforms like Reddit, with the implied odds on these basically falling off the screen.

We’ve discussed how sports betting and prediction markets have comparable user bases and outcomes, but when considering parlays, the platforms that facilitate both these forms of speculation are not equipped to deal with them in the same way.

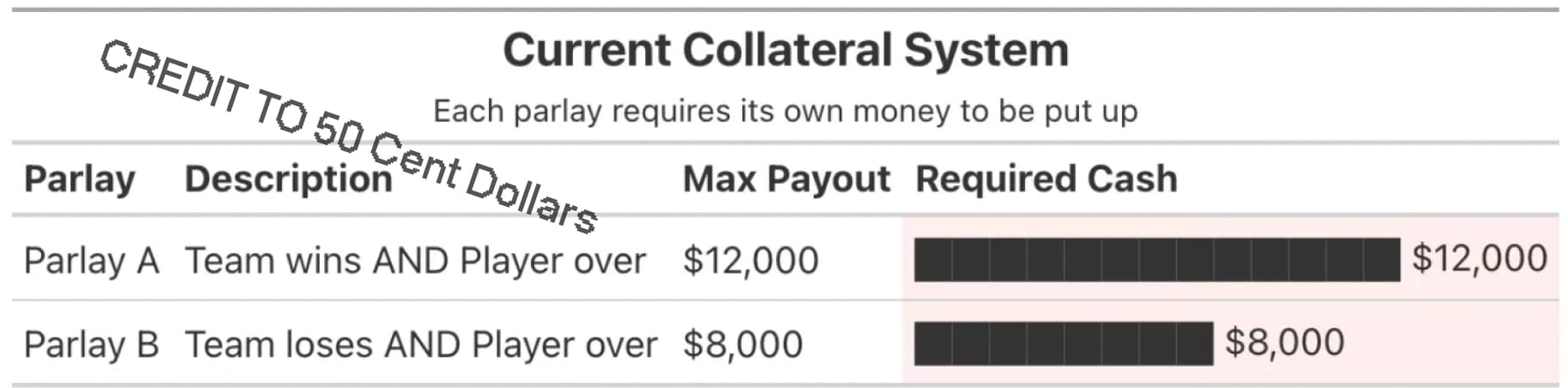

Polymarket and Kalshi must fully collateralize all of the positions on their site, meaning that if a stated open interest of $150 million is listed for each of these platforms, all of that money is made up in active positions held by traders on the platform. Sportsbooks are different, as their users are betting against the house or other market makers that pay out depending on the outcome. This crucial difference affects the liquidity available on the order book of any given event market, as the money must be posted by a market maker or user, and these parties must deposit USD or USDC (in Polymarket’s case) to place this bet.

A sportsbook might see billions of dollars in volume each day, but not all of this money truly exists, especially in the case of parlays. If a user were to put $10 down on a 12 leg parlay with odds of +192876, guaranteeing a payout of $19,287, the market maker or counterparty on the other side of the trade wouldn’t need to immediately post these funds. In the case of a prediction market, the money must be there for resolution, making parlays quite difficult considering these long-tail outcomes.

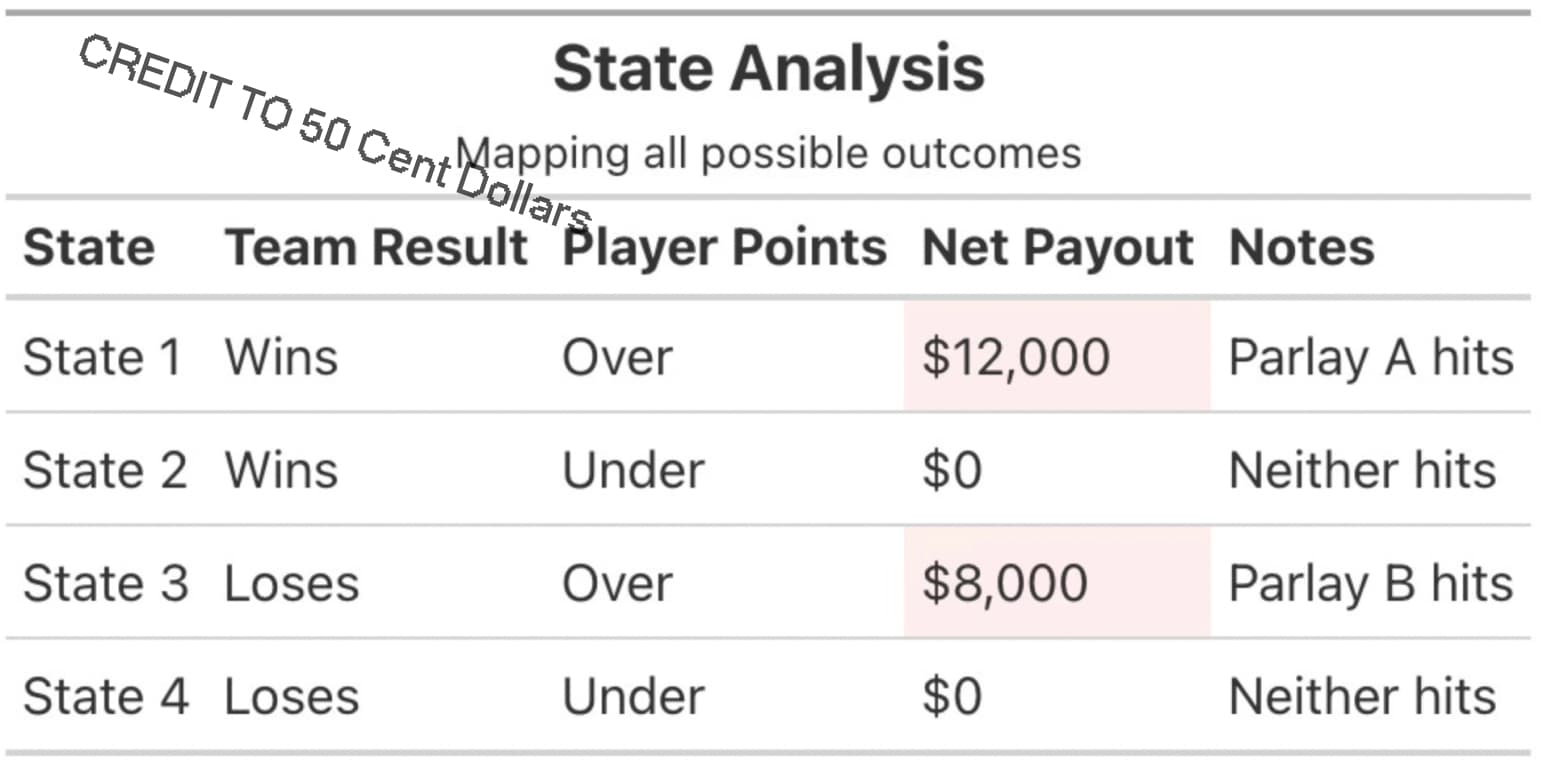

Adhi Rajaprabhakaran provided data on this here, using a basic hypothetical under the assumption a prediction markets platform would see usage on par with the average sportsbook:

“Quick math: when a user stakes $S at +X odds, the counterparty must have $S × (X/100) of cash at risk. So a $5 bet at +100,000 ties up $~5,000 on the other side, because you get to buy ~5000 shares of YES (at 0.1¢ each). Do that a lot, and the numbers stop being charming. If you accept a 2 million parlay tickets in a day with a realistic mix of odds, the aggregate cash market makers would need to post runs to high hundreds of millions — and if the long tail gets fatter, billions.”

The takeaway is that “small shifts toward the longshots explode collateral needs” making it almost impossible for existing market makers to accommodate even a small amount of parlay demand. Taking on even 5-10% of traditional parlay demand would make capital requirements skyrocket for market makers, an unnecessary burden to place on them considering the previously discussed difficulties of adverse selection, volatility, and inventory risk associated with prediction markets.

If a cash-backed prediction market platform wanted to offer parlays, Adhi listed three potential steps to take, each of which still representing a much more watered down version of sportsbook parlays:

-

Sharply limiting stake sizes in the tail

-

Funneling users into a small menu of pre-made parlays

-

Getting permission to margin portfolios instead of ponying up for every worst‑case payout up front

No matter which direction taken, the end result is still a vastly less exciting parlay experience relative to sportsbooks’ “pick-your-own” model and would be void of typical lottery-style parlay outcomes that users crave. Kalshi has done parlays before but only on specific or pre-approved markets, and to our knowledge, Polymarket has not yet explored parlays of any kind. Kalshi’s foray into parlays so far can be categorized under the second option, pre-made parlays that are designated for users keen for more risk, but still a far cry from a traditional sports parlay.

One interesting aspect of Polymarket’s on-chain presence is the potential for a third party to offer up this infrastructure themselves, essentially creating a platform where users could trade and build parlays via on-chain Polymarket contracts, managing the risk themselves. It’s not clear whether an approach like this would be viewed kindly by the CFTC, and its existence would be more in-line with the origins of crypto’s DeFi industry than anything existing today. This would probably not be endorsed by Polymarket directly in any scenario, but it’s hard to imagine them not at least entertaining the idea.

Kalshi would be unable to do this, and if a third party tried to attempt the above example, it would resemble an OTC business more than another DeFi protocol, making it unlikely to gain traction and full of other regulatory risks.

This discussion shines light on the currently broken collateral system of prediction markets, where market makers must put up funds equivalent to the worst-case outcome, ignoring the obvious that two different resolutions are mutually exclusive and you don’t need to over-insure on a scenario that’s statistically (and logically) impossible.

When observing the fully collateralized nature of prediction markets from this angle, it doesn’t make nearly as much sense as it did before. The current state of market making would mean that if a five leg parlay was created between five separate markets on a platform, the worst-case of a trader hitting maybe +4528 odds in a victory would need to be insured against, even though our fearless speculator here might only be putting up $15 on the bet.

The incentives are simply not aligned for a market maker if they’re forced to put all of their capital stack to work on highly unlikely events instead of using it in other prediction markets separate from parlays, ones that would give them much greater capital efficiency. While this full-collateralization mandate is still in place, it’s hard to imagine parlays rolling out anytime soon, leaving us skeptical of their immediate role in competitive dynamics between both of these platforms.

While parlays might be the dominant method of boosting payouts in the sports betting world, leverage is the easiest way of doing this in crypto.

Earlier we displayed a graph of top crypto exchanges’ respective futures volumes, with monthly totals coming out to trillions in USD terms. Perpetual futures are popular due to their range of leverage, though the number ultimately depends on the exchange and the relative liquidity of an asset. Something like BTC, ETH, or SOL may offer up to 100x leverage, whereas a less liquid token would cap out at 3-5x leverage. This is significant but also poses great risk, even for experienced traders.

Implementing leveraged prediction markets would be tricky and arguably more complicated than the parlay structures just discussed. This relies on prior knowledge of market makers’ risk appetite and the challenging role of managing inventory risk considering one side of the market is bound to trade at $0 upon resolution. Market making in leveraged prediction markets would amplify these difficulties, and even if it would be great for speculative users, it is a completely uncharted territory for any existing counterparty.

Leverage has yet to be explored by either Polymarket or Kalshi, most likely because these platforms are still working out the kinks of spot market making, but potentially due to the extremely high 1,500% annualized volatility credit to @defiance_cr sof prediction markets.

Volatility is just one factor to consider, as the natural structure of a binary prediction market makes it that liquidity not so gradually dissipates from one side of the book as an outcome gets closer to resolution (100% or 0% probability). John Wang’s post discussing prediction market perps on Hyperliquid laid out potential solutions, like liquidation bands, leverage decay prior to expiry, rate limiting oracles, and pre-settlement auctions.

Some of these are better than others, and we agree that liquidation bands and leverage decay should be the norm for quite some time in the early phases. The post is good but possessed one flaw I wanted to pick out, particularly concerning scalar markets:

“Scalar markets settle to a range, such as CPI percent or BTC dominance, instead of 0 or 100. This materially reduces jump risk and supports higher leverage.”

Scalar markets are still subject to binary resolution, even if these are ranges rather than binary YES or NO options. The issue doesn’t come from how a prediction market is presented, but how it concludes, and all of these resolve in the same, zero-sum way. Even if scalar markets present themselves as different due to their continuous nature, the price converges to one side and jump risk does exist, especially for markets that rely on a signal from a third party (like CPI prints).

It’s possible for safe leverage ratios to roll out over time, but nothing on the scale of crypto’s perpetual futures market would be possible, let alone outside of the top 25-30 markets on these platforms. Keep in mind that leverage for Solana memecoins has yet to be solved, despite the crypto industry’s fascination with perpetual futures - it’s simply a tough financial engineering problem and leveraged anything should be handled with the utmost precaution.

The leverage and parlays question is relevant because of claims that prediction markets just don’t pay enough or that locking capital up for three months or longer is simply bad R/R in a market environment like today’s. While more qualitative in nature, these claims are absolutely true, and it should not have taken this long to address the elephant in the room.

Coming from an industry where coins can spawn with a $150 million market cap and grow to nearly 15x sthat on billions of volume in a matter of three days, many of the prediction market payouts are comparatively weaker, though this shouldn’t come as a surprise. It’s a fairly recent phenomenon where parlays constitute a significant chunk of sports betting activity, partially due to a prior lack of accessibility, but potentially because of the a href="https://oldcoinbad.com/p/long-degeneracy" target="_blank" style="pointer-events:auto; position:relative; display:inline-block;">growing trend of rampant speculation amongst younger generations.

Regardless of how frequent this sentiment may appear, prediction markets are unfit to contend with the raw excitement present within sportsbooks - even Kalshi - until these improvements are made.

Forms of manipulation and historical accuracy analysis

Since we’re going to be discussing market settlement and accuracy of these markets prior to resolution, it’s best to provide a brief explainer on how these platforms actually handle dispute resolution and settlement in their own unique ways.

Brief aside on oracles

In Polymarket’s case, the UMA oracle manages settlement and dispute resolution in a way that requires arguably zero human oversight. The UMA protocol is an optimistic oracle and dispute arbitration system that brings in vast amounts of data on-chain, overseen by a committee of UMA token holders.

To quote Polymarket and UMA’s documentation:

“UMA’s Optimistic Oracle allows contracts to quickly request and receive data information … The Optimistic Oracle acts as a generalized escalation game between contracts that initiate a price request and UMA’s dispute resolution system known as the Data Verification Mechanism (DVM). … All contracts built on UMA use the DVM as a backstop to resolve disputes. Disputes sent to the DVM will be resolved within a few days — after UMA tokenholders vote on what the correct outcome should have been.”

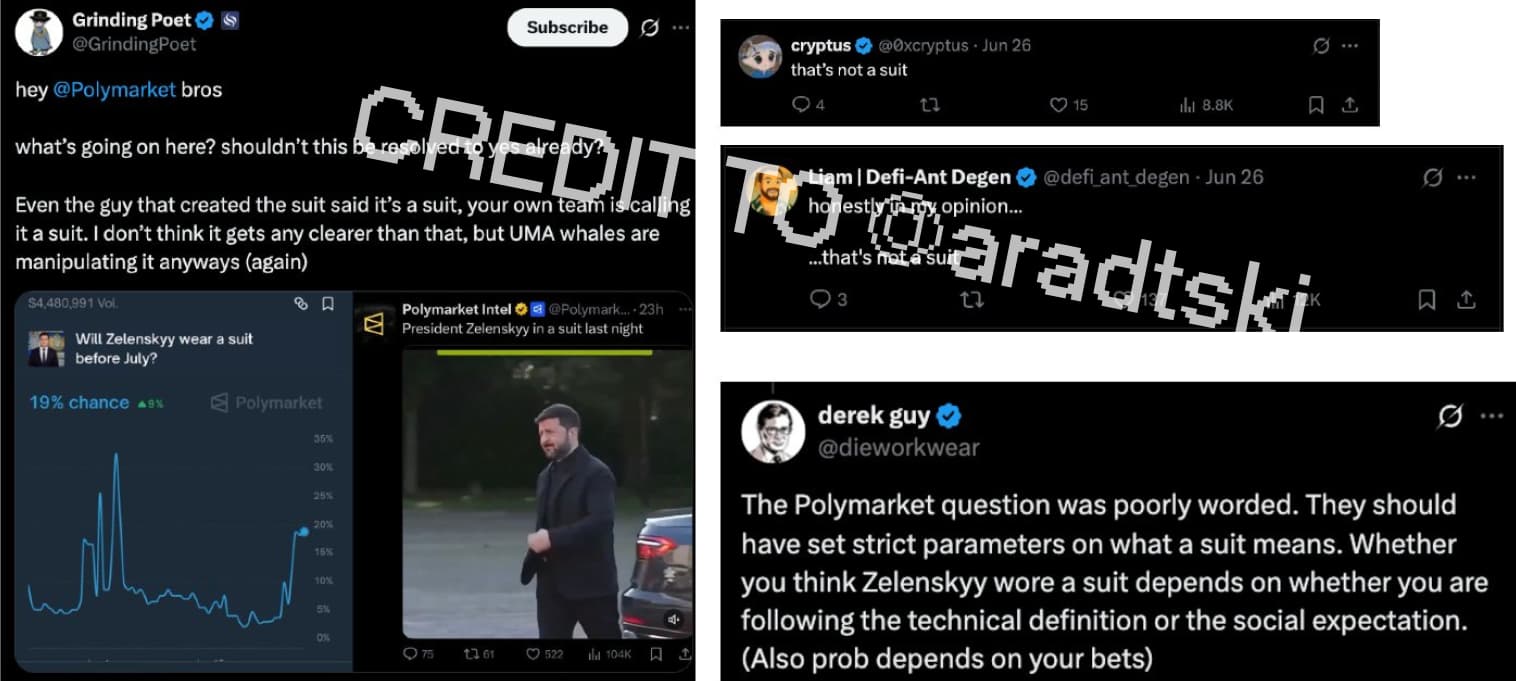

Polymarket’s most recognizable controversy stemmed from its “Will Zelensky wear a suit before July?” market which caused a stir due to the questionable attire worn by Zelensky and whether or not it could be deemed a suit. This specific market did over $242 million of volume before resolving to no, but led to significant debate across all parts of X, as it seemed pretty obvious Zelensky had worn some type of suit.

There are many other examples (nice list laid out by @aradtski here) unique to Polymarket, but the Zelensky problem stands out because it’s a resolution that everyone saw with their own eyes, yet failed to capitalize on given the authority of UMA’s oracle and Polymarket’s internal ruling. UMA is a crypto native protocol but has gained significant recognition primarily through its work with Polymarket.

“The Oracle Problem is not really the oracle problem, because crypto oracles were never designed for such things as world events” or put in simpler terms, UMA is simply unfit to manage the governance process of Polymarket in its current state, handling hundreds of millions of dollars each month.

Kalshi doesn’t face this issue as they have an internal team for market review and dispute resolution, and even if this work is slower than an oracle’s more automated approach, it has more than likely saved them headaches and bad press. Kalshi makes use of a dedicated markets team that handles internal review and dispute resolutions, though it’s worth noting they may utilize similar data sources as Polymarket, but are potentially more defensible against controversy despite this slower approach.

Resolution scandals could be considered manipulation, though ideologically they are more similar to a bug in the platform’s design. On the other hand, manual manipulation - done with intent - can be considered a feature and is achievable through a number of unique ways. There aren’t many proposals to improve existing oracles or any significant alternatives being worked on, but it’s something to keep your eye on if the more technical side of prediction market infrastructure interests you.

Manipulation, crime and some caveats

Historical accuracy of prediction markets was just discussed, but this concept must be revisited from a newer, non-academic angle. Whether or not you ascribe to the view that prediction markets are more accurate than mainstream media, polling data, or other sources of truth is besides the point: manipulation is not only measurable, but arguably already an issue.

We propose two different types of manipulation - social coercion and insider arbitrage -, as well as an explanation on how whales and large traders may or may not be contributing to this, with data to confirm our view.

Suppose there exists a high-ranking executive at Universal Music Group that wants to understand how the public feels about a new Drake album. Maybe internal polling and data suggests this album would do well, but they aren’t certain. They ask an employee in the hypothetical marketing or data science department to spin up a simple, multi-outcome market on Polymarket, titled something like “Drake’s first week album sales?” and offer up a small amount of liquidity.

Maybe the range of outcomes includes <1.5 million, 1.5 million-2 million, 2 million-2.5 million, >2.5 million. From here, you could pretty reasonably gauge consumer expectations around Drake not only as an artist, but from the perspective of an investment. The multi-outcome market isn’t just bored traders staking money on the success or failure of an album, but rather the aggregated beliefs of numerous market makers and potentially well informed music fans putting their money where their mouth is

Going back to the accuracy of prediction markets, it’s easy to argue even an illiquid market (or this hypothetical) gives more value to an opinion when the alternative is a set of random individuals polled with no methodology of gauging their internal views or knowing if they told the truth or not.

Let’s say previous hypothetical markets for artists like Taylor Swift, Olivia Rodridgo or Ed Sheeran had made headlines and been viewed tens of millions of times across platforms X, creating a mini-marketing wave of their own in the process.

Our hypothetical record label executive then decides that, in order to juice week one sales and drive a narrative that Drake’s new album is red hot, Universal Music Group will sway the orderbook in overwhelming favor of the highest week one sales, to a degree that anyone seeing it will be forced to take note of Drake’s upcoming album.

This will obviously cost the record label, but in this scenario, it’s a decent way of sparking buzz and creating headlines that has yet to be done by anyone else, and it’s probably cheaper than a corporate marketing campaign typically attached to an artist of Drake’s caliber.

If you’re a more astute reader, you’ll notice a problem with this hypothetical: if one entity singlehandedly purchases a large chunk of >2.5 million contracts, wouldn’t the market’s natural forces return this back to some sort of equilibrium and fair value?

This is not only correct, but it’s already been tested and proven to be the case, though market size for this hypothetical and the real world example are quite different.

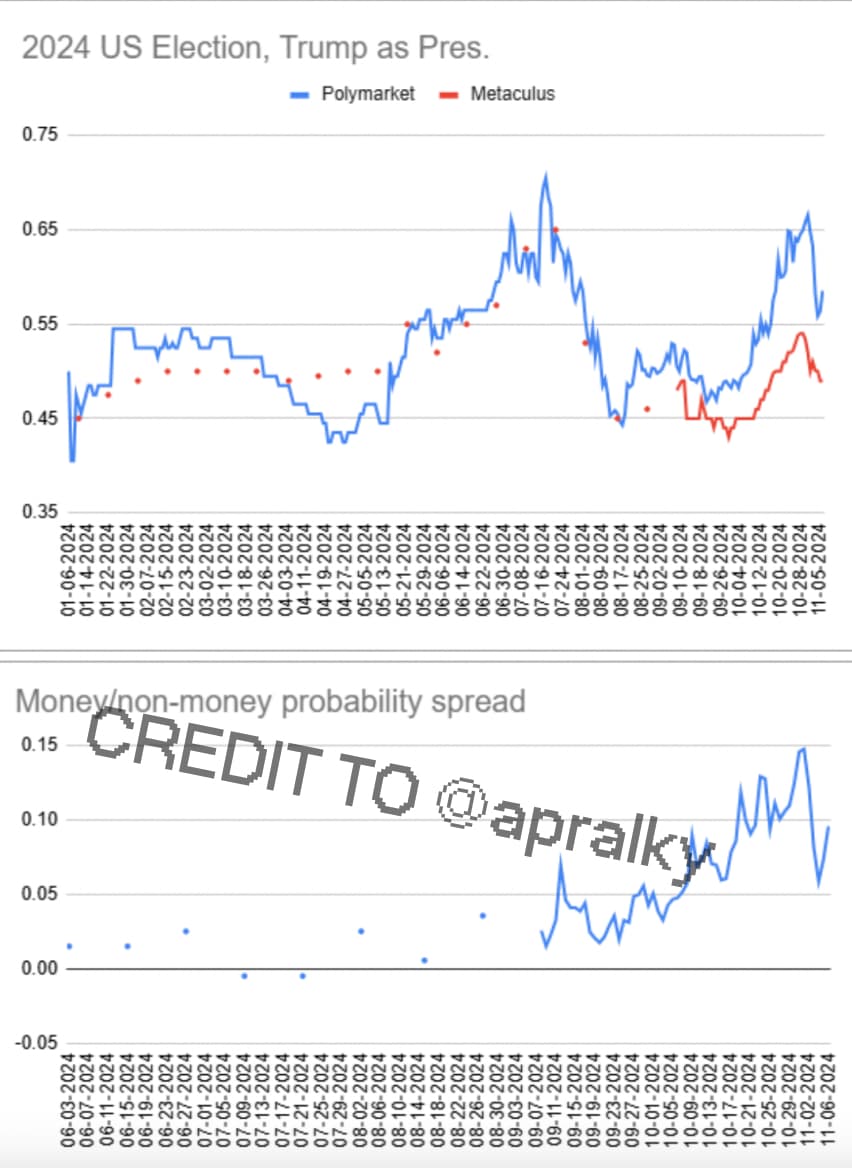

Posted on X by @apralky (otherwise known as Yung Macro) in June of this year, this analysis pokes at the holes in Scott Alexander’s arguments, specifically the claim that whale skew is responsible for Polymarket’s inflated 2024 US Presidential Election odds assigned to Trump.

Scott wrote that money-based prediction markets priced Trump’s odds of winning far higher than non money-based prediction market platforms (like Metaculus ), seemingly caused by whales’ bets skewing the odds beyond “fair value.” Scott proposes a counter-argument, as well as a counter to the counter-argument, but we will only look at the objective truth.

Regardless of whether or not a whale skewed the odds from fair value (54% Trump win probability) to something 8-10% higher (62-64% Trump win probability), the reality is that this market did not correct the overzealous whale and return to a hypothetical fair value. In fact, Yung Macro’s data shows that the spread between money and non-money platforms did not collapse back to fair value and widened over time.

If traders believed a whale was skewing this market beyond reality, sellers would have taken advantage of this and brought the price lower over time, and the pre-whale price would have come back to the market. This did not occur, and it’s illogical to run with this narrative when the data says otherwise. Put simply, the market did its job and expressed the beliefs of traders even in the face of experts claiming otherwise.

This phenomenon was most observable in the distinction between Polymarket and the mainstream media’s coverage of the election, with CNN reporting how platforms like Polymarket saw something they didn’t. But it’s far more likely Polymarket itself didn’t see anything at all, rather the hivemind trading on it expressed their raw beliefs and backed them with dollars.

Aashish Reddy echoed these claims, arguing that “They self-correct at the margin, because any mispricing attracts those who can profit by correcting it: when the price drifts from reality, the next trader to act is disproportionately likely to be someone who recognises the error, and their trade pushes the market back towards truth.”

Without being overly reductive, we see this phenomenon in traditional finance occasionally, where a company might blow earnings estimates out of the water and pop in price +20/30% after hours, only to correct itself the next day.